The Kabbalistic Vision: The Tree of Life and the Living Word

Kabbalah, meaning “receiving” or “tradition,” is among the most intricate and enduring expressions of Western mysticism. It began not as a single text or movement, but as a current within Judaism—a contemplative attempt to understand how the Infinite could reveal itself through creation. In its earliest stirrings it drew upon merkavah mysticism, the visionary tradition of Ezekiel’s chariot, where the prophet beheld the whirling wheels of the divine throne. Later writings deepened these visions into a metaphysics of emanation. Every letter of Scripture was understood as a vessel of divine energy, every word a mirror of the ineffable.

By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, in Provence and Spain, this hidden current coalesced into a formal system of speculation. The Zohar, attributed to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai but composed by Moses de León and his circle, became its luminous center. Written in an ecstatic Aramaic, the Zohar speaks of the Divine as endless radiance—Ein Sof—flowing outward through ten emanations or Sephirot. These emanations form the Tree of Life, the inner architecture of creation. The Zohar declares, “The light which illumines all worlds issues from the Infinite, and from that light all things are nourished.”

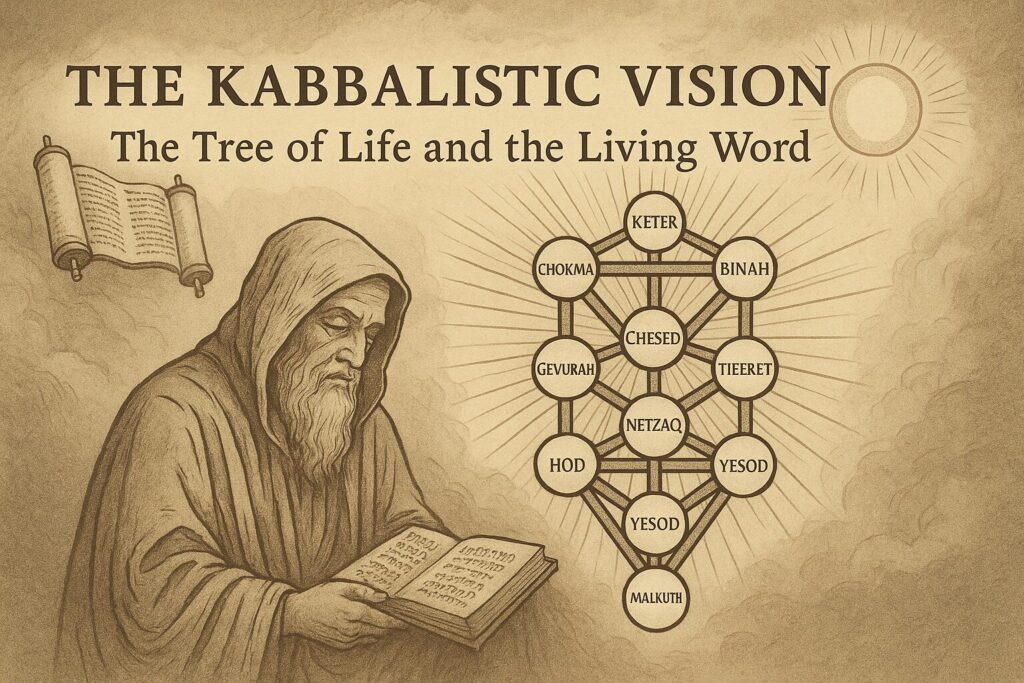

The Tree is not a diagram of hierarchy but of relationship. The Sephirot unfold from unity to multiplicity, from pure potential to manifested world, each reflecting a divine quality: Keter (Crown), Chokmah (Wisdom), Binah (Understanding), Chesed (Mercy), Gevurah (Severity), Tiferet (Beauty), Netzach (Victory), Hod (Splendor), Yesod (Foundation), and Malkuth (Kingdom). To contemplate them is to trace the descent of divine energy into form and the ascent of the soul back toward its source. “To know the ten Sephirot,” said later commentators, “is to walk the path by which the world was made.”

Kabbalah thus joined devotion to philosophy. Its practitioners sought not mere knowledge but transformation—the purification of the heart through meditation on divine names, letters, and symbols. Traditional teaching restricted it to mature scholars already grounded in Torah and Talmud, for the mystic ascent was considered dangerous if attempted unprepared. To gaze too early upon the chariot was to risk madness or death; only the disciplined mind could bear the radiance of unity.

When the Renaissance dawned, Kabbalah crossed linguistic and cultural boundaries. In fifteenth-century Italy, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola encountered Hebrew mystical texts through Jewish teachers and saw in them the key to a universal theology. He believed that Moses and Plato, Kabbalah and Christianity, expressed one hidden wisdom. “There is no science,” he wrote, “that more surely persuades us of the divinity of Christ than true Cabala.” For Pico and his followers—Johann Reuchlin in Germany, Athanasius Kircher in Rome—the Tree of Life became a diagram of divine order corresponding to the Christian Trinity, angelic hierarchies, and cosmic creation.

This Christian Kabbalah translated Hebrew symbolism into a language that could survive within the Church. The ten Sephirot became reflections of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; the divine names were harmonized with Christological mysteries; angels replaced the Hebrew emanations as mediating intelligences. The blending was audacious but sincere—a philosophical attempt to reconcile revelation and reason, Scripture and geometry.

Through Hermetic channels, the Tree of Life entered the wider world of esotericism. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw Kabbalah interlaced with alchemy, astrology, and Rosicrucian speculation. By the nineteenth, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn restructured it into a comprehensive magical system. Each Sephirah was assigned a planet, color, divine name, archangel, and Tarot correspondence. The Tree became a map of initiation: from Malkuth, the material plane, the adept ascends through successive levels of consciousness toward Keter, the crown of union.

Aleister Crowley inherited this synthesis and expanded it. In 777 he charted hundreds of correspondences between the Sephirot, planets, deities, and sacred texts. For him, the Tree was both mystical and psychological—a way to understand the structure of the soul. “The Universe is a tree,” he wrote, “and every man is the fruit thereof.” Crowley’s Thelema, with its doctrine of True Will, found in the Tree a perfect symbol of divine manifestation through individuality.

The Tree of Life can be read as both macrocosm and microcosm. The upper triad—Keter, Chokmah, Binah—represents pure divinity, the archetypal realm beyond form. The middle group—Chesed, Gevurah, Tiferet, Netzach, Hod, Yesod—structures the moral and spiritual dynamics of creation. The lowest, Malkuth, is the world made visible, the field of action and embodiment. The Sephirot are linked by twenty-two paths, each associated in Hermetic systems with a Hebrew letter and a Tarot trump. To travel these paths in meditation—an exercise called “pathworking”—is to enact the ascent of consciousness. The practitioner visualizes movement upward through the Sephirot, integrating their qualities: mercy with strength, beauty with wisdom, until opposites resolve in unity.

Each Sephirah is also attended by angelic hosts and divine names, balanced by its shadow or Qliphothic counterpart. The Qliphoth (“shells”) are the residue of creation, energies that have lost equilibrium. They are not evil in essence, but incomplete, echoing the creative power without harmony. Later occultists treated them as infernal spheres, but the mystic sees them as reminders that holiness and imbalance are twin possibilities within the same current of force. In witchcraft, these distinctions soften into a continuum of spirit. Angelic intelligences may appear as guiding presences; Qliphothic currents may be understood as chaotic but instructive powers, catalysts for self-knowledge. This interpretive openness is not dilution but participation in the Hermetic principle of holy syncretism: one truth speaking many languages.

As with Hermeticism, the perception of Kabbalah was shaped by class and culture. Jewish Kabbalists, often scholars or rabbis, occupied a respected if cautious position within their communities. Their writings circulated among learned circles, not among the general faithful. Christian Kabbalists, protected by patronage, were admired as philosophers. But the same societies that honored learned mystics condemned folk healers and witches. A rabbi meditating on divine names was venerated; a peasant woman murmuring charms was feared. Both worked with invisible forces, yet gender and literacy defined the boundary between sanctity and sorcery.

The Hermetic-Qabalistic current shaped nearly every modern magical order. The Golden Dawn’s Tree became a universal key to correspondences: each planet, element, and Tarot card found its place upon it. Thelema reinterpreted this as a map of the soul’s evolution, where every Sephirah corresponds to a stage of awakening. The Theosophical movement expanded Kabbalistic ideas into a universal metaphysics of evolution, while Carl Jung read alchemical and Kabbalistic imagery as symbolic of psychological integration—the process he called individuation. Wicca, though arising from a different lineage, absorbed these currents almost unconsciously. The casting of the circle, the invocation of the quarters, and the recognition of layered worlds echo the Kabbalistic understanding of descent and ascent, of worlds within worlds. Many witches today use the Tree as a meditative map: Netzach aligned with Fire, Hod with Water, Yesod with Air, Malkuth with Earth. In this way, the cosmic diagram becomes a mirror of natural cycles, a bridge between mystical philosophy and embodied craft.

Kabbalah offers many contemplative practices adaptable to both mystical and magical paths. Pathworking invites the imagination into visionary ascent along the Tree. Chanting the divine names associated with a Sephirah—such as El in Chesed for mercy, or Elohim Gibor in Gevurah for disciplined strength—aligns the practitioner with its virtue. Meditation on the Tree itself can reveal patterns of imbalance or integration in one’s own life, for the human psyche reflects the structure of creation. Yet the tradition demands respect. Jewish Kabbalah is a living sacred study; its symbols carry centuries of theological meaning. To engage it outside that context requires humility and acknowledgment of lineage. The Hermetic and witchcraft adaptations are not replacements but parallel expressions. Each stream draws from the same divine source but speaks in its own tongue.

Kabbalah, like any system of mystical ascent, contains hazards. To approach the Tree purely intellectually is to mistake the map for the territory. Memorization of correspondences is no substitute for inward transformation. Contact with Qliphothic energies without balance can destabilize emotion and thought. Attempting to merge incompatible theologies without understanding can produce confusion rather than synthesis. The Zohar warns: “The light of wisdom burns those who draw near unprepared.” For modern seekers, discernment is the first safeguard. Study slowly. Begin with meditation on the lower Sephirot—the virtues of generosity, integrity, and harmony—before reaching toward the supernal triad. Recognize that the divine names and angelic orders are symbols of consciousness, not merely external beings. The goal is integration, not accumulation.

The Tree of Life remains one of the most profound symbols of unity in the Western esoteric tradition. To Jewish mystics, it is the inner anatomy of God and cosmos. To Christian Kabbalists, it reveals the hidden Christ within creation. To Hermetic magicians, it is the diagram of correspondence binding heaven and earth. To witches, it is the living pattern of nature’s cycles, a ladder between elements and spirit. None of these readings cancels the others. Like the caduceus of Hermes, the Tree winds its meanings upward through many ages, carrying the same current of divine intelligence. It is both cosmic and personal, eternal and immediate. When one meditates upon it, the divisions of theology and language fade, and the living world itself becomes scripture.

Kabbalah endures because it offers a vision of order infused with mystery. It teaches that the Infinite flows into form and that every act of creation is a reflection of divine will. It reveals a universe composed not of accidents but of relationships—letters, numbers, colors, angels, and elements all bound within one radiant pattern. For witches and mystics alike, the Tree of Life can serve as a sacred map. Where the Kabbalist perceives Sephirot and angels, we may perceive the forces of nature, deities, or spirits. Where the mystic warns of the Qliphoth, we may recognize the necessary shadows that balance light. This is not appropriation but continuation: the same quest for unity expressed in new idioms.

At its summit, the Tree returns to Ein Sof, the boundless mystery. To climb it is to retrace the divine descent, restoring awareness to its source. Whether one names that source God, Goddess, or simply the Living Spirit, the path is the same—an ascent through knowledge, love, and devotion toward the One that breathes through all things. Kabbalah remains a living vision of creation, an ever-branching testimony that the world is filled with sacred meaning. To study it is to receive, and in receiving, to give back light to the Infinite from which all light proceeds.