Spellcasting

Every spell is a question cast into the living fabric of the world. To practice magic is not only to will change, but to listen to the echo of that will — to read how the universe receives, reflects, or redirects the energy sent forth. In this way, spellcasting itself becomes a form of divination: an art of revelation as much as transformation. What we call results are often responses. What we interpret as outcome is also oracle.

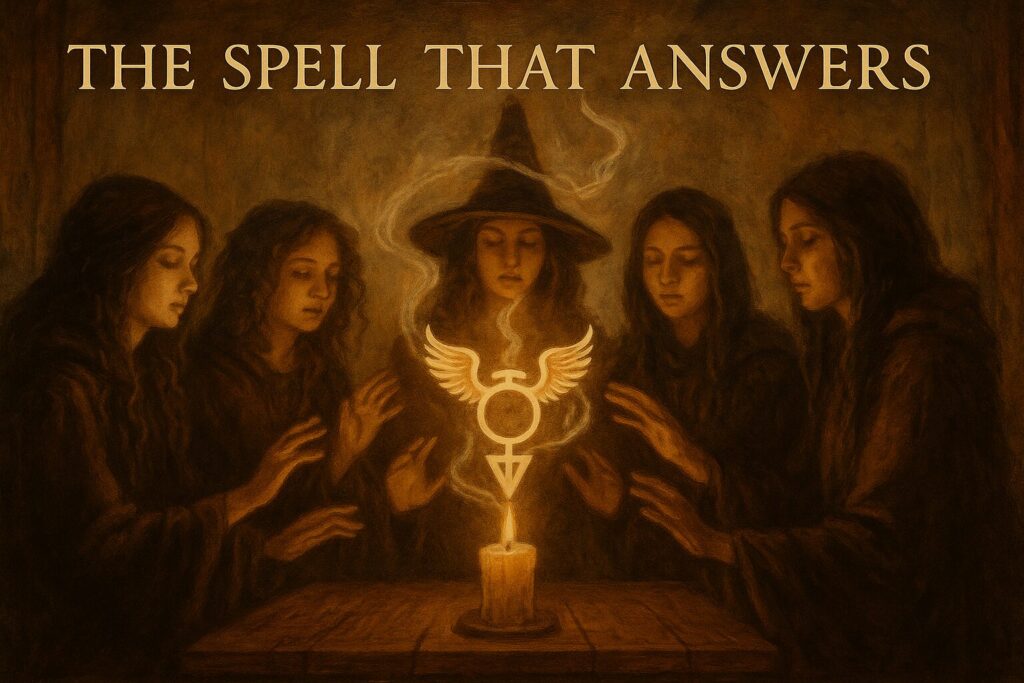

Divination and spellwork are sometimes treated as twin but separate disciplines — one receptive, one projective. Yet in the deeper currents of the Craft, they spiral around each other like the serpents of the caduceus, one drawing power downward from the divine, the other raising understanding upward from the material. Both are acts of communication. Both rely on symbols, timing, and intention. Both seek not to dominate reality but to converse with it.

From the earliest magical traditions, casting and divining were never divided. The Babylonian priests who read omens in smoke also burned sacred herbs to invoke their gods. The oracles of Delphi entered trance not only to foresee but to embody Apollo’s word — their prophecy was itself a ritual performance. In folk magic, the charm or spell was simultaneously an experiment and a reading: if the candle burns clear, the spirit consents; if it sputters, the way is blocked. The result of the working revealed the will of the unseen. Thus, every enchantment became a mirror.

In the Wiccan and witchcraft traditions, this principle endures. When a witch performs a spell — to heal, to attract, to release — she is also listening. The movement of flame, the timing of signs, the sequence of coincidences afterward all speak as eloquently as cards or runes. The ritual itself becomes a divinatory process: the spell is cast outward like a question, and the world replies through pattern. The circle becomes a dialogue between will and wyrd — between the self’s desire and the greater intelligence that enfolds it.

This understanding transforms the purpose of magic. It ceases to be merely operative and becomes revelatory. The practitioner does not impose intent upon an indifferent universe; she engages in correspondence with an animate one. A candle that refuses to light may indicate resistance or misalignment. A spell that works too swiftly may reveal deeper readiness than expected. The process is diagnostic, the outcome instructive. In this sense, the witch’s laboratory is also her oracle.

Such divinatory spellwork can be cultivated deliberately. The practitioner might craft workings not solely for effect but for response — for example, a spell of calling that asks, “What forces are truly aligned with my goal?” The materials chosen — herbs, colors, planetary hours — become questions encoded in form. The manifestations that follow, whether in dreams, synchronicities, or tangible shifts, are answers decoded through intuition. A simple candle working can thus serve as both catalyst and compass.

The psychological dimension reinforces the mystical one. To cast a spell is to externalize inner intention, to make thought visible through ritual form. In doing so, the unconscious speaks. The gestures, words, and tools become a symbolic language through which the deeper self communicates with waking awareness. Observing how the spell unfolds — what emotions arise, what obstacles appear, what insights follow — reveals the psychic landscape in motion. The magic works on the caster as much as it works on the world.

This is why seasoned witches often describe their practice as listening magic. The spell’s first purpose is not control but communion. The materials of the craft — wax, flame, salt, water, feather, stone — are not inert props but interlocutors. The divine speaks through texture, resistance, and transformation. A bowl of water clouding unexpectedly or a sigil refusing to catch fire are not failures but messages. Each working becomes a correspondence course in the language of the living world.

Within coven settings, this principle becomes collective divination. When multiple witches raise energy for a common purpose, the way the energy moves, the visions that arise, or the sensations felt across the circle all serve as auguries. The spell’s flow reveals the group’s alignment, the balance of will and harmony among members, even the readiness of the moment. Afterward, divination may confirm what was already known through experience: that the magic itself spoke as it was cast.

In this way, spellcraft closes the false divide between action and insight. Every act of will is also a form of observation, every invocation a kind of reading. The distinction between “casting” and “consulting” dissolves; the spell becomes the medium through which the world answers the witch’s heart. This understanding deepens ethical practice as well: if each act of magic is a conversation, then respect and listening become the foundation of power.

For example, a practitioner might work a charm for protection and find it inexplicably difficult to finish — materials spilling, timing thwarted. She could force the completion or pause to ask, “What is this resistance telling me?” The delay may reveal a hidden cause — a friendship draining energy, a location unsafe for ritual, or a fear unresolved. The spell has already worked, though not as expected: it has disclosed truth before effect.

Thus, the witch learns that divination is not merely preparation for spellwork, but its essence. Every casting contains its own augury. Magic, when understood as dialogue, becomes self-correcting, self-teaching. The practitioner is no longer a commander of unseen forces but a participant in their pattern, a listener to the sacred feedback loop of creation.

In this light, divination and spellwork cease to be different arts and are revealed as two movements of one current — one inhaling, the other exhaling; one receiving, the other sending; both inseparable from breath itself. For what is magic, if not the act of asking the universe to speak — and what is divination, if not the realization that it always answers?