Occult and the Esoteric

When we speak of the occult, we enter a word that has long dwelt in shadow—reviled, misunderstood, and yet quietly luminous beneath its layers of misrepresentation. Its syllables hum with secrecy: occultus, the Latin for “hidden,” “concealed from sight.” The occult is not merely what is dark; it is what is unseen. It concerns those properties of existence that cannot be weighed or measured yet reveal themselves to the attentive soul: the magnetism in the lodestone, the virtue of a leaf, the resonance between the movements of planets and the stirrings of the human heart. In the Renaissance, philosophers and natural magicians spoke easily of these “occult virtues,” meaning forces not evident to the senses but present in the secret sympathies of nature. To study the occult was not to flee from light, but to seek the deeper light—the illumination hidden behind appearance.

The word esoteric offers a kindred vibration, though it turns inward rather than downward. From the Greek esōterikos, “inner” or “belonging to the within,” it names the knowledge meant for initiates, the teachings whispered beyond the temple’s outer gate. In the ancient mystery cults of Greece and Egypt, such knowledge was never forbidden—it was simply safeguarded, veiled in symbol so that only those prepared by experience might apprehend it. The Eleusinian initiate did not learn the mystery; they became it. Thus the esoteric points toward the architecture of understanding, while the occult points toward the practice of unveiling. One is the map of the inner cosmos; the other is the journey through it.

Together they form a pair of mirrors. The occult is the art of working with hidden forces, the esoteric the philosophy that interprets them. Both demand reverence, study, and transformation. Both depend upon secrecy, not out of arrogance, but out of respect for the potency of the unseen. To rush the unveiling is to destroy the very conditions by which mystery nourishes meaning.

Throughout history, cultures have known and named their hidden arts. In Kemet, priest-magicians preserved the sciences of divination and the soul’s passage, writing of them in hieroglyphs meant to conceal as much as to reveal. In India, the Upanishads were the “sitting near,” reserved for those ready to hear what could not be spoken to the many. In Celtic lands, the druids wove their wisdom into triads, riddles, and songs, carried mouth to ear across generations. In each tradition the pattern holds: there is knowledge exoteric, given to all, and knowledge esoteric, given in trust. The boundary between them is not elitism but initiation—the testing of the heart’s readiness to hold what cannot be uttered lightly.

In the craft we practice, these terms are not relics of dusty scholarship but living symbols. To call something occult is to acknowledge the sanctity of the hidden, the necessity of shadow in which power germinates. Witchcraft itself was once the folk expression of the occult—those quiet arts of healing, blessing, and banishment that thrived in hedgerows and kitchens long before they were named by theologians. The cunning woman, the wise man, the midwife, the herbwife—each tended to the unseen threads binding body and spirit. They practiced the occult in its purest sense: working with the invisible harmonies of life.

The esoteric, meanwhile, lives in the coven’s circle as the pattern that informs our practice—the web of correspondences, symbols, and mythic frameworks that lend meaning to our rites. When we trace the pentacle, we echo ancient diagrams of microcosm and macrocosm. When we call the quarters, we reenact a cosmology of elements that is both philosophical and embodied. This is the esoteric heart of the craft: not a dry system of signs, but a living grammar of the sacred. We inherit these languages from Hermeticism, from Kabbalah, from the philosophers who sought to map the invisible worlds; yet we weave them into our own practice, translating intellect into invocation, symbol into song.

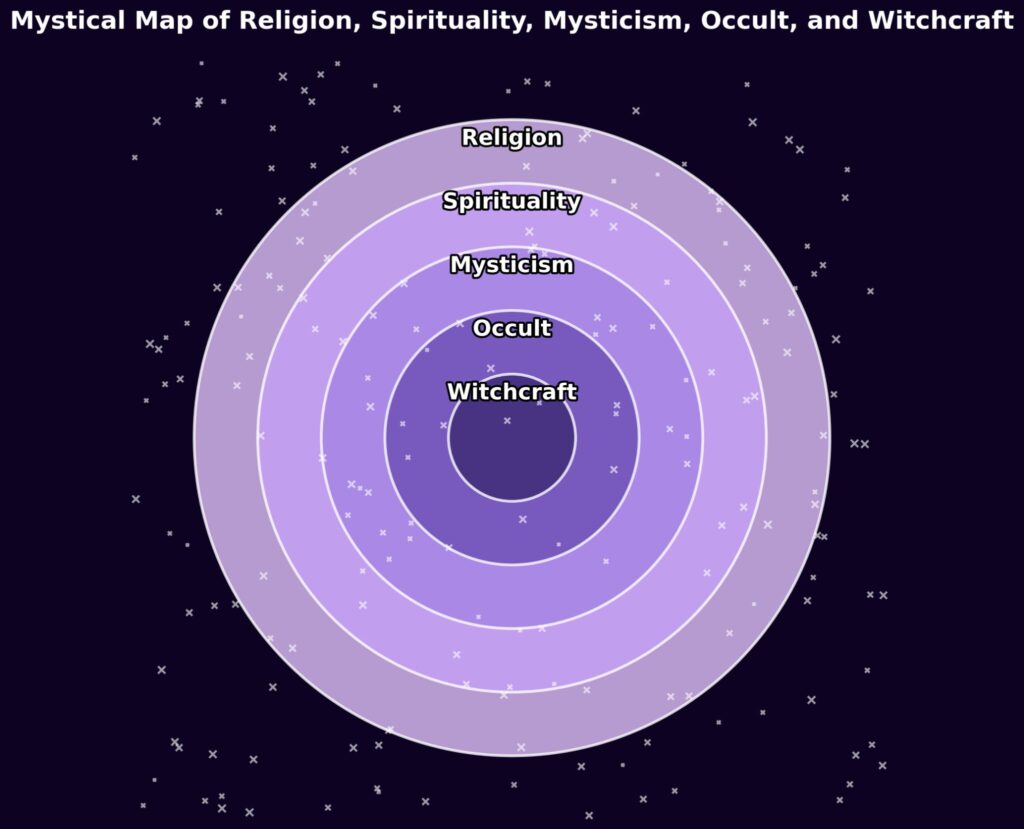

We, as witches, dwell where the occult and the esoteric meet. Our art is neither pure scholarship nor pure instinct, but a rhythm between them. We study the correspondences, the planets, the sigils, the sacred alphabets—but we also kneel in the soil, feeling how the unseen pulse of the earth answers the movement of our own breath. The occult without the esoteric can become superstition; the esoteric without the occult can become sterile abstraction. Together they form the twin pillars between which the witch walks.

Modern Wicca stands precisely upon this threshold. It is both religion and craft, both inherited and invented, both ancient in soul and modern in form. Its founders drew from ceremonial magic—the esoteric frameworks of Hermetic and Rosicrucian lore—and from the older, earthbound witch-traditions of Europe. In the Great Rite and the Wheel of the Year, in the Goddess and the God, we find mythic structures that are at once mystical and philosophical: the interplay of polarity, balance, and return. Yet within this architecture burns the living fire of the occult—the casting of circles, the raising of power, the transformation of energy through will. Wicca’s genius is that it united these streams: the scholar’s geometry of spirit and the witch’s visceral dance with it.

To reclaim the words “occult” and “esoteric” is to reject centuries of fear. For too long they have been bound to the imagery of heresy and horror—the devil’s pact, the black mass, the blasphemous book. But the true current beneath those words is luminous. To be occult is to seek the hidden life of things; to be esoteric is to perceive the inner law that orders the cosmos. Both are paths of reverence, not rebellion. The witch who gathers herbs by moonlight and the philosopher who writes of emanations and spheres are companions upon the same road: each tending to a different face of the invisible.

The hidden is not the forbidden. It is the fertile. Every seed germinates in darkness before it rises into light. So too the knowledge we call occult or esoteric must root in the depths before it can bloom into wisdom. To walk this path is to honor what cannot be spoken in haste—to understand that secrecy is not deceit, but devotion to the mystery that sustains us.

We, who call ourselves witches, children of the moon and students of the hidden art, move beneath the veil not to flee from the world, but to love it more completely. For the world is veiled only from the unseeing. To those who walk in wonder, every stone, every wind, every heartbeat is occultus—hidden, yes, but radiant to those who know how to look. And in that seeing, we find our craft: the living bridge between the unseen and the seen, between the mystery that dreams and the life that answers it.

“That which is above is like to that which is below, and that which is below is like to that which is above, to accomplish the miracle of the One Thing.”

— The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus

Some Notable Occult and Esoteric Orders

A selective lineage of hidden societies and their echoes in modern witchcraft. (Inclusion ≠ endorsement.)

| Order / Society | Founded / Origin | Key Figures | Core Focus / Teachings | Major Works / Texts | Overlap with Witchcraft / Wicca |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn | 1888, London (UK) | W. W. Westcott, S. L. MacGregor Mathers, W. B. Yeats, A. Crowley | Hermeticism, Qabalah, ritual magic, Enochian currents | The Golden Dawn (Israel Regardie); “Flying Rolls” (internal papers) | Circle casting, elemental quarters, degree structure and ritual grammar echoed in early Wicca |

| Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.) | c. 1906, Germany/UK | Aleister Crowley, Karl Germer | Thelema, ceremonial magic, esoteric sexuality, liturgy | The Book of the Law (Liber AL); Gnostic Mass (Liber XV) | Liturgical cadence and some Thelemic philosophy influenced syncretic Wiccan lines |

| Argenteum Astrum (A∴A∴) | 1907, UK | Aleister Crowley, G. C. Jones | Individual attainment, Qabalistic pathworking, yoga/magick synthesis | The Equinox; Magick in Theory and Practice | Interior training models, graded work, and diary discipline adopted by some Wiccan covens |

| Theosophical Society | 1875, New York (USA) | H. P. Blavatsky, H. S. Olcott, Annie Besant | Comparative mysticism, karma, reincarnation, esoteric evolution | Isis Unveiled; The Secret Doctrine | Popularized Eastern ideas that permeated modern pagan/Wiccan cosmologies |

| Rosicrucian Currents (incl. S.R.I.A., AMORC) | 17th c. (manifestos), later revivals | Mythic C. Rosenkreuz; R. Fludd; modern: W. W. Westcott, H. Spencer Lewis | Christian Hermeticism, alchemy, symbolic reform | Fama, Confessio, Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz | Hermetic-alchemical worldview feeding the occult revival that shaped Wiccan symbolism |

| Builders of the Adytum (B.O.T.A.) | 1920s, Los Angeles (USA) | Paul Foster Case | Tarot–Qabalah synthesis, color and pathworking | The Tarot: A Key to the Wisdom of the Ages; B.O.T.A. lessons | Modern tarot symbolism and meditative practice widely used by witches |

| Fraternitas Saturni | 1926, Germany | Gregor A. Gregorius | Saturnian initiation, astro-magical rites, Thelemic inflections | Magie der Eingeweihten (Gregorius) | Influences planetary/astrological magic strands in occult witchcraft |

| Martinist Order | late 18th c., France | L.-C. de Saint-Martin; M. de Pasqually | Esoteric Christianity, reintegration of the soul | Treatise on the Reintegration of Beings (Pasqually); Saint-Martin’s letters | Mystical interiority adopted by some witches in contemplative work |

| Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor | late 19th c., UK/Europe | Max Théon; (influence) P. B. Randolph | Practical occultism, astral/psychic training | The Light of Egypt (T. H. Burgoyne) | Methodological precursor to Golden Dawn; techniques echoed in ritual witchcraft |

| Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia (S.R.I.A.) | 1865, England | Robert Wentworth Little, W. W. Westcott | Rosicrucian Kabbalah, Christian Hermetic study | Collectanea (S.R.I.A. papers) | Shared personnel/ideas with GD; part of the ritual genealogy Wicca drew upon |

| Alpha et Omega (GD offshoot) | 1903+, UK | S. L. M. & Moina Mathers | Continuation of GD initiatory and ritual corpus | Ritual manuscripts (private); surviving papers published in parts | Carried GD current forward into 20th-century occult revival |

| Order of the Temple of the Rosy Cross | 1890s–1900s, France/UK | Stanislas de Guaita, Joséphin Péladan | Symbolist occultism, ceremonial aesthetics, Kabbalah | de Guaita’s La Haute Magie; Péladan’s La Décadence Latine cycle | Influenced continental occult aesthetics informing eclectic witchcraft |

| Order of Nine Angles (O9A) | 1970s, UK | “Anton Long” (pseud.) | Extreme LHP, transgressive esotericism | NAOS; Hostia (controversial texts) | Outside Wicca; referenced only for context; studied critically, not as lineage |

| Temple of Set | 1975, USA | Michael Aquino | Setian philosophy, self-deification, ritual psychology | The Book of Coming Forth by Night; Aquino’s works | Minimal overlap with Wiccan ethics; relevant in comparative esotericism |

| Alice Bailey / Lucis Trust (Arcane School) | 1919–1930s, USA/UK | Alice A. Bailey | Theosophical-derived esotericism, spiritual psychology, “rays” | A Treatise on Cosmic Fire; Discipleship in the New Age | Diffused metaphysical ideas (energy centers, planetary hierarchy) into New Age & eclectic witchcraft |