Rekindling the Sacred: A Neopagan Reflection on Spirit, Philosophy, and the Divine Manyfold

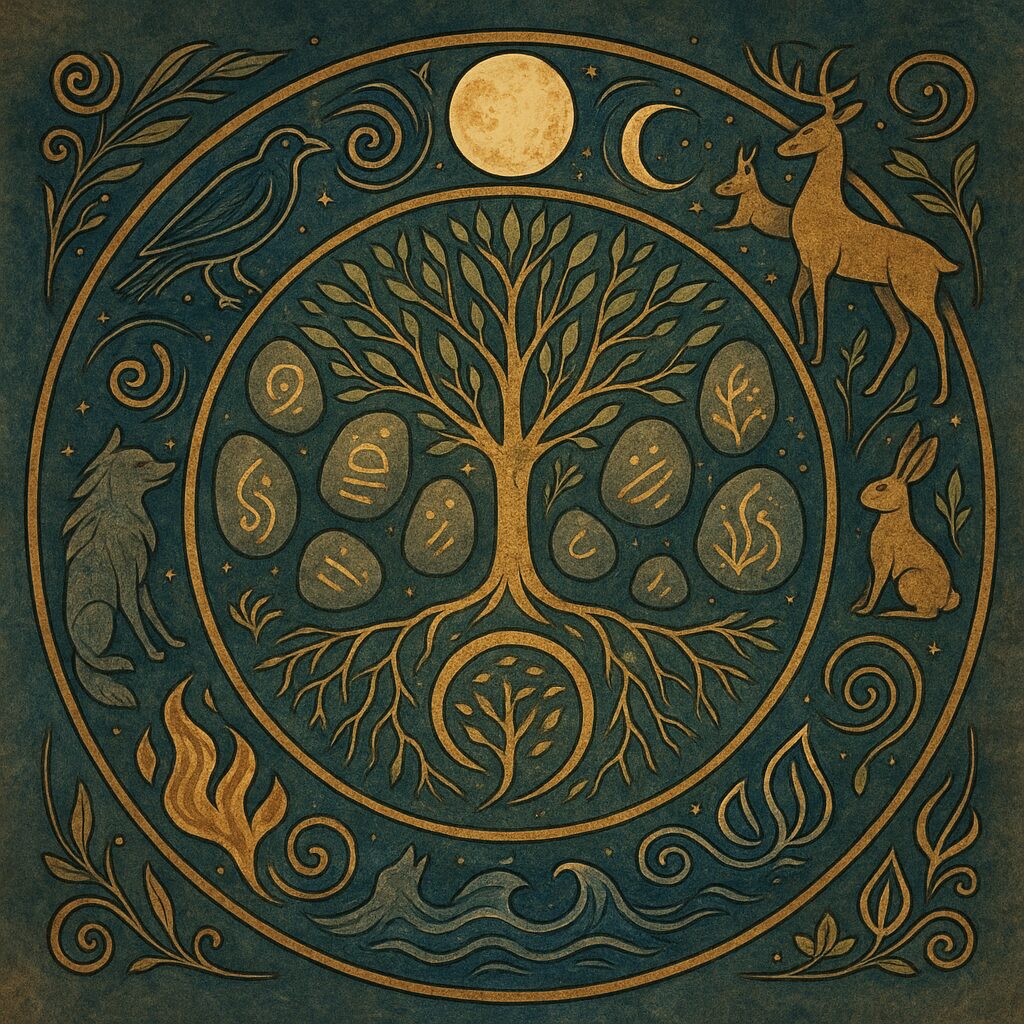

Neopaganism is not a return, but a remembering. It is not about reviving what once was in perfect form, but instead listening for echoes—in trees, in dreams, in the rhythms of the land—and weaving those fragments into something living. Neopaganism is not a singular tradition, but a family of spiritual paths that reach back to pre-Christian, polytheistic, animistic, and nature-reverent traditions—while speaking with the voices of those who live today.

For many of us, this is not a hobby or rebellion, but a sacred act of reconstruction and re-enchantment. We walk alongside the gods not because we have blind belief, but because we have known their presence in ritual, in grief, in joy, and in the wind. In a time when the world feels severed from meaning, Neopaganism restores the great tapestry: of myth, of cosmos, of spirit, of kin.

This essay seeks to honor that path by exploring its roots, its philosophy, its contrasts with monotheism, and the ways in which ancient mysteries and modern science now seem to whisper the same truths. It is written for believers—curious, seasoned, wandering, or wise—and for those who feel the Old Ones watching from behind the veil.

Monotheism did not arrive gently. While we may respect those who walk Christian, Muslim, or Jewish paths today, we must acknowledge that the rise of monotheistic religions was also the story of erasure: of temples burned, of women silenced, of spirits recast as demons, and of gods relegated to “myths.”

Yet fragments survived.

In folktales, in faerie stories, in whispered charms, in the still-practiced offerings to the dead, we find the resilience of the old ways. These echoes, once dismissed as superstition, are in truth cultural fossils of polytheism. Across the British Isles, Scandinavia, the Baltic lands, Slavic forests, and Mediterranean coasts, the bones of the old gods lay just beneath the surface.

Neopaganism rises not to re-enact those exact rites—but to reweave meaning from those strands. It is not about nostalgia. It is a spiritual archaeology, grounded in modern life, but rooted in ancestral memory. Scholars like Ronald Hutton remind us that what we call “ancient” is often reconstructed—but that does not make it false. All religions are constructed. The sacred is not less sacred because it is remembered, only more human.

In contrast to monotheistic traditions which speak of a singular, all-powerful deity, Neopaganism embraces a plurality of divinity. The gods are not simply “faces” of one being. They are beings in themselves—archetypal, yet real. They are not omnipotent but relational—they are part of the cosmos, not beyond it. They evolve, they change, they can be fierce or tender, just like the natural world.

As Starhawk writes, “The Goddess does not rule the world; She is the world.” In Neopagan thought, divinity is not remote—it is immanent, flowing through rock and water, flame and blood.

Monotheism’s great strength is clarity and unity—but it came with a cost. Historically, it brought a theology of exclusivity and hierarchy: one god, one book, one truth. Other gods were downgraded to demons, spirits were outlawed, and the Earth was seen not as sacred, but as something fallen to be transcended.

Yet even within monotheism, the cracks reveal pluralism. In Christianity, we find saints, angels, and the Holy Trinity—a divine pantheon in all but name. In Islam, the 99 names of Allah represent different aspects of being. In Judaism, the earliest texts speak of Yahweh amidst “other gods,” and the Shekhinah—the divine feminine presence—is still honored in mystical circles.

Moreover, there are spirit-beings across these traditions: angels, demons, saints, jinn. They are not the Creator, yet they act, guide, and guard—mirroring the intermediary spirits and devas of Pagan thought. In truth, what we call monotheism is more often “henotheism” (one high god among others) or monolatry (worship of one while acknowledging others).

In choosing polytheism, we are not choosing chaos—we are choosing relationship. With many gods, there are many ways to be. No one deity speaks for all of life, and the diversity of divinity mirrors the diversity of human and natural experience. The world is not ruled by one father—but dances with many forces.

Neopagan metaphysics begins with a simple claim: the world is alive. Rocks dream. Trees speak. Fire remembers. Spirit infuses all things—not as metaphor, but as presence. This is a return to animism, the belief that all entities possess soul or consciousness.

This stands in contrast to Cartesian dualism—the dominant Western philosophical mode—that separates mind from body, spirit from matter. Neopagans hold that matter itself is sacred, not just a vessel but a voice.

Time is not linear but cyclical, echoing the seasons, the moon, and the soul’s own unfolding. Death is not an end, but a gate.

There is no Neopagan Ten Commandments. Instead, we live by relational ethics: what is right flows from right relationship—with gods, kin, land, and self. The Wiccan Rede (“An it harm none, do what ye will”) and the Law of Threefold Return are examples of intuitive, reflective guidance—not rigid law.

Neopagan ethics often emphasize:

- Personal sovereignty: You are your own sacred center.

- Responsibility: Power must be tempered by awareness.

- Reverence: Not just for gods, but for the ecosystem of being.

- Hospitality and consent: Especially in spirit and faerie work.

We are not perfect beings striving toward abstract salvation. We are woven into the world, and our task is to honor the threads.

Neopagan traditions speak often of “the Otherworld,” “the Veil,” or “the Spirit Realm”—realms where the gods dwell, where ancestors walk, and where faeries linger. These are not fanciful metaphors but vital components of our cosmology.

Rather than a flat heaven/earth/hell model, Neopagan cosmology imagines interwoven layers of reality: physical, astral, ancestral, divine, fae. Shamans, witches, and mystics have long known that these realms overlap with our own—available through trance, ritual, and dream.

Modern physics has begun to describe realities that echo ancient spiritual cosmologies. String theory proposes that we live in a universe with 10 or 11 dimensions—only four of which we can perceive. M-theory suggests that our universe may be a membrane (“brane”) floating in a multidimensional space.

We do not claim this proves the fae exist—but it resonates. What shamans called the spirit world, physicists now describe as higher dimensions inaccessible to our normal senses. When a witch says, “the veil is thin,” she speaks of a boundary between dimensions, a threshold science is only beginning to name.

As Carl Sagan once said: “The fact that some geniuses were laughed at does not imply that all who are laughed at are geniuses. But it does suggest that some ideas are ahead of their time.”

Neopaganism honors spirits of place, the fae, ancestors, elementals, and devas—beings that move between the worlds. They are not gods, yet they are mighty. They are not human, yet they touch us.

We do not own them or command them. We build relationships—with offerings, respect, and care.

Compare this to:

- Angels: messengers and guardians in Abrahamic faiths.

- Jinn: in Islam, free-willed spirits that live beside us.

- Saints: human souls elevated to divine intercessors.

In each case, humans instinctively seek intermediaries, spirits who can be called upon, petitioned, befriended. The line between Pagan and monotheist cosmologies is not one of kind—but of permission and framing.

Neopaganism is not a single tradition. It includes:

- Wicca: formalized by Gerald Gardner and expanded by Doreen Valiente and Starhawk; honoring the God and Goddess, the Wheel of the Year, and ritual magic.

- Reclaiming Tradition: ecofeminist and political, rooted in activism and personal sovereignty.

- Druidry: inspired by Celtic revival, focusing on bardic arts, trees, and the sacred land.

- Heathenry and Norse Paganism: honoring the Aesir, Vanir, and ancestral values.

- Eclectic and Solitary Paths: drawing from many wells, tailored by intuition.

These movements do not agree on everything. That is their power. Multiplicity is not confusion—it is freedom.

To be Neopagan today is to resist the erasure of sacred multiplicity. It is to say: the world is still holy. The gods were never banished. The spirits are still singing.

It is also to confront the shadow of colonization. Monotheism spread hand-in-hand with empire, often suppressing indigenous, land-based, and feminine-centered spiritualities. Neopaganism must be careful not to appropriate others’ traditions in its hunger for authenticity. Instead, we must root deeply in what calls to us ancestrally, relationally, and responsibly. The Earth does not need us to copy every past rite. It needs us to stand in sacred reciprocity again—to listen, to reweave, and to live as if the world is alive. Because it is.

Neopaganism is not simply belief—it is practice, philosophy, presence, and poetry. It is imperfect, evolving, often messy. But it is real.

It says:

- There is no one truth—but there is truth in relationship.

- The world is not fallen—it is beloved.

- Gods are not jealous—they are plural.

- We are not broken—we are becoming.

We walk this path with dirt on our feet, fire in our breath, and songs older than memory.

The gods are not waiting to be proven. They are waiting to be remembered.

Blessed be the sacred manyfold.