Thelema – The Fire of True Will

Thelema arose from the threshold between old aeons, at once a continuation of Hermetic wisdom and a radical break from it. In the early years of the twentieth century, Aleister Crowley—poet, magician, and scandalous prophet—proclaimed that the world had entered a new era of spirit. Having passed through the disciplines of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, where he mastered the Qabalah, astrology, ceremonial magic, and Enochian conjurations, he turned his initiation inside out. Tradition, to him, was no longer a ladder to climb but a chrysalis to break.

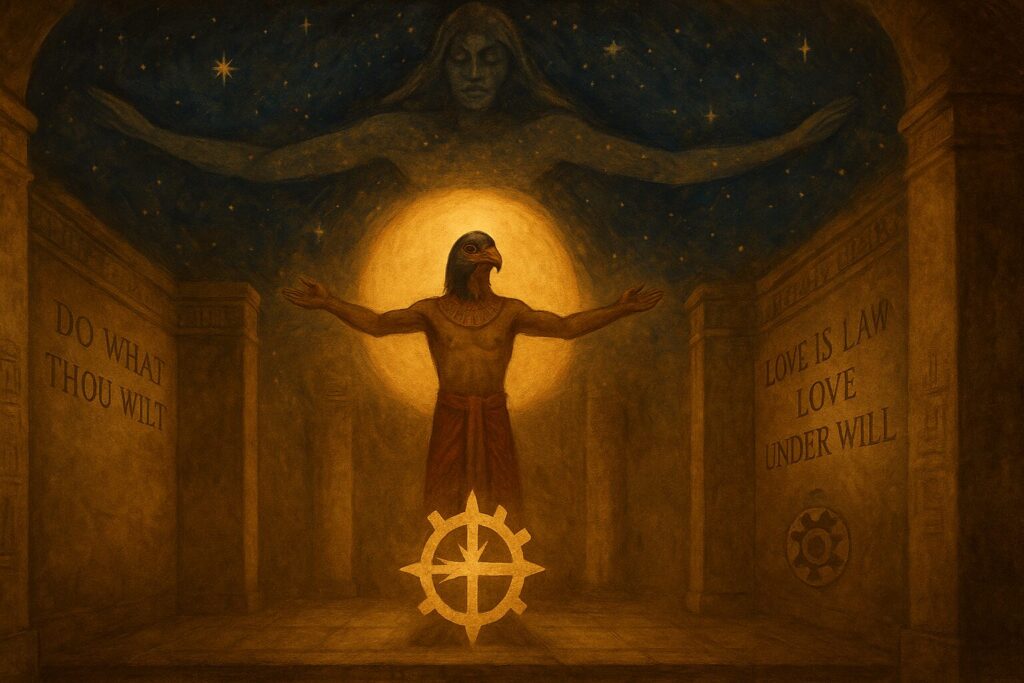

In Cairo in 1904, during a curious sequence of visionary events, Crowley’s wife Rose became the vessel through which a being called Aiwass dictated to him Liber AL vel Legis, The Book of the Law. This slim but volcanic text announced the Law of Thelema—“Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. Love is the law, love under will.” It was not a permission slip for impulse but the unveiling of a new metaphysic: that the divine expresses itself through every individual’s True Will, and that the fulfillment of this Will is the sacred task of existence.

Crowley named this new dispensation the Aeon of Horus. The child-god, crowned and conquering, symbolized the awakening of self-realization after the long ages of submission and sacrifice. The old Aeon of Osiris—identified with Christianity, with its hierarchies of sin and redemption—was to yield to a solar, liberated consciousness. Yet the remnants of Christian thought persisted in his vocabulary: angels, demons, gods, and sacraments survived, now charged with new valences. Where the Church had divided heaven from hell, Crowley saw a spectrum of energies—forces of creation and dissolution to be invoked, integrated, or transformed according to the magician’s True Will.

Thelema’s cosmology is a trinity of motion: Nuit, the infinite star-goddess arching over the cosmos; Hadit, the infinitesimal spark of consciousness within each being; and Ra-Hoor-Khuit, the union of both—the active child of infinite potential made manifest. Around this triad spin the familiar orbits of Qabalistic correspondences, planetary rites, and Tarot symbolism, all re-interpreted through the lens of the New Aeon. Crowley’s Thoth Tarot distilled this fusion of Egyptian myth and Hermetic structure, making image the language of initiation.

Unlike Hermeticism’s quiet philosophers or witchcraft’s village priests, Crowley built orders: the A∴A∴ as a path of solitary attainment, and the O.T.O. as a vehicle for ritual community. These were esoteric aristocracies rather than folk gatherings—intellectual, theatrical, and deliberately shocking. Modern witchcraft, emerging decades later through Gerald Gardner, would invert that model, bringing ritual to the hearth and the coven circle. Yet Gardner borrowed liberally from Crowley’s material: gestures, invocations, and the very architecture of the circle echo Thelemic ritual. The two currents—Thelemite and Witch—flow alongside one another, sometimes mingling, sometimes wary, each seeking to reconcile freedom with form.

The practice of Thelema weds mysticism to discipline. Daily adorations to the Sun—Liber Resh—align the practitioner with cosmic rhythm. The rituals of the Pentagram and Hexagram, inherited from the Golden Dawn, purify and invoke the elemental and planetary powers. The Gnostic Mass celebrates the marriage of spirit and matter in liturgical pageantry, while yoga and meditative concentration anchor the ecstatic into the physical. Even the invocation of spirits—angelic or chthonic—is reinterpreted as psychological and cosmic dialogue rather than superstition. To summon a demon, for Crowley, was to face an aspect of one’s own unconscious will; to call an angel was to commune with the higher genius guiding that will.

For witches, this spectrum resonates deeply. Thelema’s spirits are neither moralized nor abstract; they are intelligences in motion, mirrors of human power. A practitioner might adapt Thelemic pentagram rites into circle work, or infuse spellcraft with the triadic symbolism of Nuit, Hadit, and Horus—cosmic, individual, and manifest—thereby joining the macrocosm and the microcosm in every act of enchantment.

But Thelema is perilous ground. Its exaltation of Will can inflate the ego it seeks to transcend; its hierarchies can breed authoritarian excess; its daemonic symphony can overwhelm the unbalanced psyche. The aspirant must temper the fire with humility, discernment, and grounding in the world of ordinary things. Crowley himself warned that “the mind must be trained to move with mathematical precision and absolute control.” Without that rigor, the magician becomes consumed by the very forces he hoped to command.

And yet, despite its perils, Thelema endures as one of the defining currents of modern magic. Its principle of True Will has seeded Wicca, ceremonial lodges, chaos magic, and the language of personal spirituality itself. It is a syncretic art: Egyptian myth interwoven with Qabalistic geometry, Enochian resonance, yogic stillness, and even Christian sacrament transfigured into new meaning. It stands as proof that the spirit of the age is never static—it mutates, devours, and renews.

In the end, Thelema offers a paradox: freedom that requires discipline, divinity discovered through the self, love that is law. It reminds the witch and the magician alike that every star has its orbit, every will its course, and that the highest act of magic is to find one’s path and walk it with integrity.