The Living Word: Language, Symbols, and Magic

Language is not merely a tool for describing reality; across cultures and historical periods, it has been understood as one of the primary means by which reality is shaped, ordered, and sustained. Creation myths, religious traditions, and magical systems alike repeatedly return to the idea of the Word — spoken, named, or inscribed — as a creative act. To speak is to differentiate. To name is to call into presence. To write is to preserve will beyond breath and body. In this sense, language functions as one of humanity’s oldest magical technologies: a structured means by which meaning, authority, and intention are made durable in the world. Magical alphabets, ritual scripts, and coded writing traditions arise from this deeper recognition that letters are not neutral marks, but vessels through which power, memory, and relationship are carried.

Word, Names, Creation, and Precision

Across cultures, language is treated as more than a tool for description. It is repeatedly framed as a creative act: the spoken Word that calls order from chaos, the utterance that differentiates what is from what is not, the naming that draws a thing into recognizability. Even when these claims are expressed through mythic idiom—gods speaking worlds into being, sacred sounds shaping matter—they point toward a durable human insight: reality is not only encountered, but made intelligible through language, and intelligibility itself exerts force. Speech organizes attention; attention organizes action; action reorganizes the world.

This is one reason “the Word” so often sits near divinity. The theological language differs—Logos, sacred speech, divine breath, creative command—but the recurring logic is that creation is not brute emergence alone; it is emergence under an ordering principle. Language becomes one of the most accessible images for that principle because it is how humans participate in ordering: we gather the unformed into concepts, we bind concepts into sentences, and we send those sentences outward as requests, vows, judgments, blessings, and warnings. A culture does not need to call this “magic” for it to function like one.

Names concentrate this power. A name is not merely a label attached to a thing; it is a point of address. To name is to distinguish, and to distinguish is to establish boundary. In many magical traditions, a name operates as a handle by which relationship becomes possible: you can call, invoke, pray, petition, command, praise, or condemn because a name fixes a target within the field of attention. This is why stories of “true names” appear so widely: they dramatize a real mechanism. The more precisely something can be addressed, the more precisely it can be engaged.

Precision follows naturally. If language is treated as operative—if words are the method by which intention is articulated, stabilized, and transmitted—then exactness matters. Grimoires, charms, liturgies, and mantras often insist on correct wording, timing, and pronunciation not out of superstition, but because formula is a technology: it preserves meaning across time, prevents drift, and trains the operator toward disciplined attention. Repetition is not redundancy; it is stabilization. In ritual contexts, a phrase repeated becomes a groove in the mind and a pattern in the work.

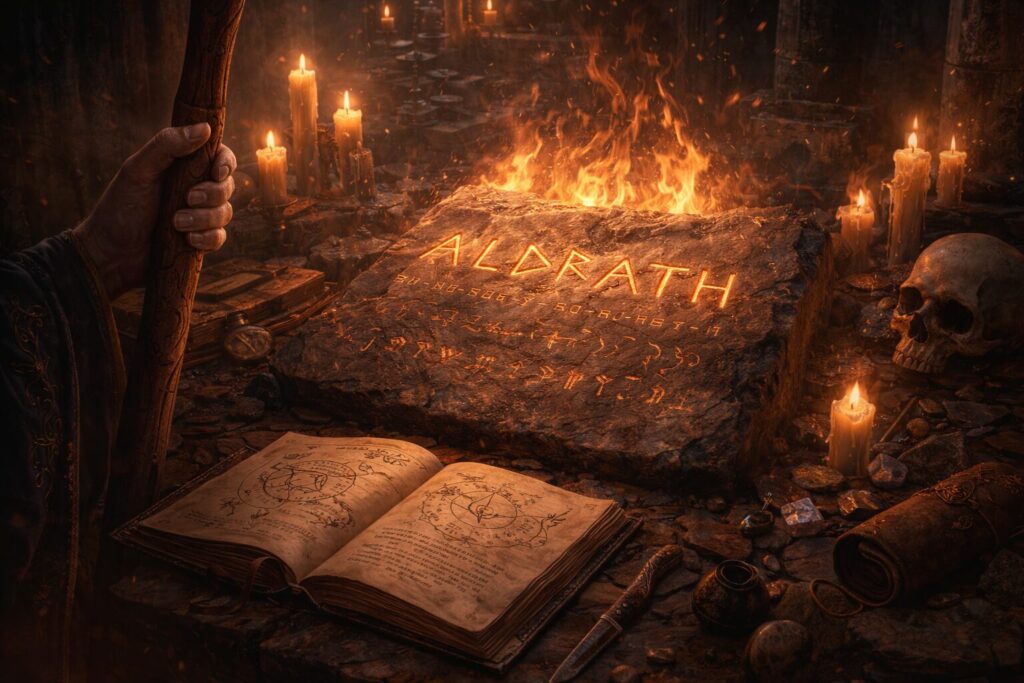

From this foundation, magical writing traditions become easier to understand. A magical alphabet is not “just a different font.” It is a way of marking language as set apart; of clothing words in ritual form; of making text behave like sacred space. Codes and ciphers, likewise, are not merely about secrecy for its own sake, but about the control of address—who can read, who can respond, and what is permitted to cross the boundary between the mundane and the consecrated.

Letters, Sounds, Numbers, and Form

If the Word names, then letters and numbers are the instruments by which naming becomes durable. In many esoteric and devotional traditions, alphabets are treated as more than neutral tools: they become correspondence systems that braid together visible form, spoken sound, and conceptual meaning. A letter is a mark on the page, a phonetic value in the mouth, and a unit within a symbolic grammar. Those three layers can be engaged separately—shape as sigil, sound as utterance, meaning as concept—or together as a single ritual technology.

This is why certain scripts acquire reputations for power. It is not only that they look “mystical,” but that they invite a different manner of attention. Writing in an unfamiliar alphabet slows the hand and sharpens intention. It introduces deliberation where casual writing tends toward drift. In practice, this can function like a consecration: the same sentence written in a ritual script often feels different because it has been made different by effort, boundary, and form.

Sound matters here just as much as shape. Spoken language is embodied vibration—breath, resonance, rhythm—and ritual cultures have long treated voice as a vehicle of presence. Prayer, chant, invocation, and mantra rely on a simple fact: what is spoken does not remain internal. It becomes pattern in the body. Repeated phrases reliably reshape attention and emotion; they train steadiness, receptivity, and coherence. Even before one argues metaphysics, voice is already doing work.

Numbers enter naturally because they describe relationship in a different key. Where letters often organize sound and concept, numbers express pattern, proportion, and recurrence—the grammar of measure by which complex realities become intelligible. This is one reason number symbolism appears so widely in calendars, ritual design, sacred architecture, and cosmology. Numbers do not merely count; they disclose structure.

In some traditions, letters and numbers deliberately interpenetrate: letters carry numerical values; names become patterns of quantity; quantity becomes another way of reading meaning. Done well, this is less “fortune cookie numerology” and more symbolic analysis—an attempt to recognize recurring forms, harmonies, and correspondences across different registers of experience. A responsible approach treats such systems as lenses rather than proofs: they can illuminate relationships, but they should not be used to bully reality into simplistic certainty.

The deeper point is craftsmanship. Letters, sounds, and numbers are all tools of precision. They are ways of giving will a stable body: form disciplined enough to hold meaning, repetition disciplined enough to hold attention, and pattern disciplined enough to hold structure. When magical alphabets are used wisely, they are not ornament; they are a practice of exactness.

Sacred Languages, Magical Alphabets, and Secrecy

Some languages come to feel “magical” because they become set apart. When a language is preserved for ritual, scripture, law, or initiation—rather than ordinary daily speech—its meanings stabilize and its sounds acquire weight. This is one reason classical or liturgical languages such as Latin, Hebrew, Greek, Sanskrit, or Classical Arabic have carried an aura of power across centuries. They function as boundary-markers: to use them is to step into a formal register where words are treated as consequential rather than casual.

In practice, sacred language behaves like ritual architecture. Fixed prayers, invocations, and formulae reduce drift. Repetition preserves nuance. Pronunciation, cadence, and context become disciplines of attention: ways of training the practitioner toward steadiness, reverence, and precision. Whether one interprets this as metaphysical efficacy or as psychological and cultural conditioning, the result is similar: stabilized linguistic form reliably shapes the operator’s state and signals that the work is underway.

Magical alphabets and ritual scripts extend this “set-apart” quality into the visual realm. Scripts such as Theban, Malachim, Celestial, Passing the River, and (in a different category) Enochian are often used to consecrate writing—to mark a page as something other than ordinary notes. In the best cases, these scripts function less like decorative fonts and more like vestments for language: they slow the hand, sharpen intention, and make inscription itself part of the working. A text becomes not only a record, but an object of practice.

The history behind this matters. For much of the past, literacy and text-production were concentrated among priestly, bureaucratic, and initiatory classes. Writing carried institutional authority: it could bind oaths, transmit law, preserve prayer, and encode procedure. That authority naturally attracted magical interpretation. If a written contract can obligate a person across time, it is not a large leap to imagine that a written charm might obligate circumstance—or that an inscribed name might hold a relationship in place.

Ciphers and coded writing traditions belong here as well, but their purpose is not only concealment. Secrecy is often a technology of boundary. It controls address—who is able to read, who is permitted to respond, and which meanings are allowed to move from the consecrated sphere into the mundane. In initiatory contexts, codes also function as gates of literacy: they require time, training, and commitment, which slows consumption and encourages seriousness. In practical terms, coded notes can protect private workings, safeguard vulnerable spiritual practices, and prevent living traditions from being flattened into content for casual spectatorship.

Done well, this stream—sacred language, ritual scripts, and selective secrecy—serves a single aim: to protect precision. The point is not obscurity for its own sake, but coherence: keeping meaning intact, intention disciplined, and practice held within appropriate boundaries. Magical alphabets, in that light, become a quiet craft—one way of making language behave as sacred space.

Magical writing traditions ultimately return to a single principle: that language is not passive. Words, letters, numbers, and scripts are tools through which human beings participate consciously in the shaping of meaning, relationship, and order. Whether through sacred speech, ritual writing, personal sigils, or carefully kept Books of Shadows, the practitioner becomes a steward of symbolic precision. The craft is not merely about exotic alphabets or hidden codes, but about disciplined attention to how language forms thought, directs will, and carries memory. To write with care is to practice magic in one of its oldest and most enduring forms — not as ornament, but as a living participation in the ongoing act of creation.

“The characters and words of divine things are not to be esteemed according to their outward sound, but according to the inward virtue and power.” -Agrippa

Explore Symbolic Practice