Kael’s Story

Field Notes From a Life Between Worlds

Neopagan Thought

Kael’s reflections, essays, and living lessons in modern Pagan philosophy.

Paganism

Roots and branches: history, streams, and cultural contexts of Pagan paths.

Practice

Ritual craft, tools, and rhythms—how philosophy becomes lived action.

Wicca

Ritual structure, ethics, and the Wheel of the Year within a Wiccan frame.

Kael staged his first sit-down strike in the third grade. It took place in the elementary school library, where he was scandalized to discover they had neither The Iliad nor Theogony. The situation escalated until the librarian contacted his mother, who—despite her surprise—simply laughed it off. From that moment forward, Kael was recognized as something of a handful. Eventually, the librarian gave in—not by procuring Homer or Hesiod, but by adding D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths to the shelves. For Kael, that book was a spark. It ignited a lifelong journey into mythology, religion, ritual, and the layered stories that form the foundation of identity—what we call the “self.”

At the time, Kael didn’t yet identify as pagan. He was a cradle Catholic, raised among saints and sacraments. But even then, he wondered: were saints truly so different from gods? For him, they formed a conceptual bridge—from the faith he was born into, to the spirituality he would eventually embrace.

Years later, his cousin Roen moved nearby. To Kael, she was a force of nature—vivid, enigmatic, and electric with intuition. They quickly became inseparable. Though they used different terms—he spoke of gods, she spoke of fairies—they shared a deep sense that the world was alive with spirits, and that they themselves were different. He, an Aries; she, a Gemini—an astrologically fitting pair. She was a waning Taurus moon, he was waxing – so another compliment in nature. The two would walk for miles to reach the hidden occult bookstore tucked beside a market strip. It was shaded, quiet, and magical. Inside, Kael found rows of books affirming the things he had sensed but never seen acknowledged. They spent countless afternoons reading, often without buying, and talking with the witches who ran the shop. Dissatisfied, his journey led him to texts such as Lewis Spence’s An Encyclopedia of Occultism, Lynn Thorndike’s History of Magic and Experimental Science, and other comprehensive works that offered entry points into older traditions. Kael soaked in survey works which later informed his own practice. The library became his mentor, teaching him how to research, how to question, how to explore.

In those first years, much of the magic Kael and Roen worked together took the form of oaths—ritual words spoken with the full gravity of belief. They were not spells in the theatrical sense, but binding agreements between two young witches who understood instinctively that intention, when witnessed, becomes power. Some of those vows were made in play, others in earnest, yet all were sealed with a sincerity so fierce that their echoes still hold. Even now, the old oaths stir at the edges of their workings.

As Kael and Roen entered adolescence, they formed their first coven of sorts—a slightly gothic affair involving planchettes, cemeteries, and genuine spiritual encounters. Around this time, Kael learned to disguise his spellcraft within the framework of Dungeons & Dragons. If his mother stumbled across a potion or a hex box, he would brush it off as “just part of the game.” But when his mother left Catholicism for evangelical Christianity, that excuse ceased to suffice. What followed were camps, interventions, and numerous attempts at deliverance by people convinced he was possessed. Their fervent hands left him with a lasting aversion to touch.

But Kael wasn’t possessed—he was just different. And insightful. Even then, he understood that much of what they were doing was its own form of ritual—an unexamined, diluted variant of pagan practice. By that point, he had read far beyond Homer and Hesiod. He had delved into comparative religion, ancient beliefs, and the porous boundaries between pantheons. He had not yet learned the term “syncretism,” but he already grasped its meaning. He also noted the paradox: the very scriptures they held sacred—both the New American Bible and the King James Version—contained traces of older gods. Their warnings only fueled his curiosity. He began seeking out the very sources they condemned. For a while he studied The Urantia Book, but found the approach presents itself as a new revelation, it remains much like Satanism, heavily rooted on Christian thought.

While others his age postered their walls with rock stars and movie idols, Kael’s bedroom was a shrine of another sort entirely. The pantheons of the Poetic Edda and Theogony stared down from his walls. What looked like eccentric nerdiness from the outside was, in truth, the earliest expression of a mind already attuned to patterns and symbols. The gods spoke to him long before he had a name for it, murmuring through stories, sigils, and the quiet synchronisms that threaded themselves through his days. Myth became his first language, symbolism his second, and together they shaped the strange, luminous interior world he would carry into adulthood.

Ironically, it was in the military—surrounded again by evangelical pressure—that Kael found temporary refuge in the Catholic Church. Sunday services allowed soldiers to avoid certain duties, and Kael, still fond of the figure of Immaculate Mary (a goddess in all but name), opted to return to Mass. Though it didn’t fulfill him spiritually, it did stimulate him intellectually. After army training, he enrolled in Catholic institutions, studying for four years with nuns and eight with the Jesuits.

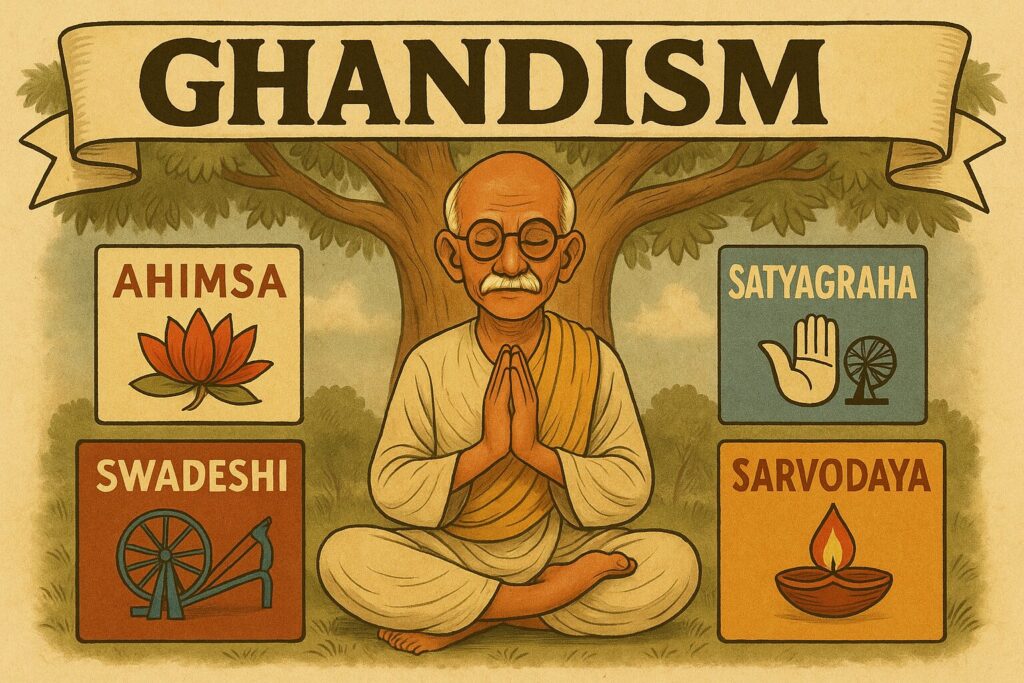

During this time, Kael’s intellectual and spiritual paths began to intertwine. He spent six months studying under a Gandhian guru, absorbing the principles of Ahimsa, Satyagraha, Sarvodaya, and Swadeshi. Politics became a spiritual calling. With the nuns, he immersed himself in Celtic Studies. He was particularly drawn to the poetry and mysticism of W.B. Yeats, which led him to explore the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the Theosophical Society, and the Order of Celtic Mysteries. Here, Kael found a confluence of history, myth, and epistemology—worldviews that resonated with his own.

He encountered many who practiced magic and ritual during this time and was introduced to Dianic witchcraft. That was a strange experience. From there, he explored Gardnerian and Alexandrian traditions before ultimately adopting a more eclectic path.

Kael earned a degree in Celtic Studies and continued on to study Classical History at a Jesuit university eventually graduating with another higher degree. There, he dove into Greek and Latin classics, studied philosophy and archival methods, and deepened his understanding of ancient texts. These tools allowed him to better grasp his inner nature and the structure of the universe—or at least, how it might be perceived. Through all of this, he found himself increasingly drawn to the gods of his youth. He became, in his own words, a pagan—but more precisely, a neo-pagan. He followed no single pantheon, instead honoring a constellation of gods drawn from various cultures and times, layered with the understanding that names change, but spirit endures.

His academic life also afforded him opportunities to travel. Among his most formative journeys was his time in Ireland, where he researched holy wells. There, myth and land fused—mounds untouched, raths and ringforts left in peace, springs that whispered, and caves that resisted entry. Though he had long known the stories, experiencing them respected in the land of their origin was revelatory. Folklore, he realized, was where myth put down roots.

Kael feels the Sidhe. He senses spirits, understands fairies, revears gods—and believes in the many unnamed presences he has encountered. Not all were kind. Some were malevolent. Most were indifferent. Some were seen – others heard. A few were ghosts. He has suffered profound loss, including death itself. Having crossed that veil and returned, he no longer doubts the spirit realm. It confirmed for him that we are far more than flesh and bone.

To Kael, there is no singular path to truth. The universe is vast, layered, and filled with mystery. Righteousness is not itself a virtue; curiosity is. And reverence—for the living and the unseen—is essential.