Crafting a Living Record of the Witch

The Living Book

A spellbook is not merely a place to store words. It is a working instrument — a technology of memory, focus, and transmission. Every serious practitioner, whether solitary or in community, eventually discovers that the craft deepens in proportion to how faithfully it is recorded. What is written is not only remembered; it is shaped, tested, revised, and made accountable.

At Coven of the Veiled Moon, we understand the grimoire and Book of Shadows as living records. They hold what has been done, what has been learned, what has failed, and what has endured. They are not aesthetic objects first and foremost, though beauty has its place. They are tools of discipline: places where practice becomes traceable, where patterns can be seen, and where magical knowledge becomes something more than fleeting inspiration.

This page is meant to serve both as philosophy and as manual. It explores why magical books have always carried power, how grimoires and Books of Shadows developed within witchcraft and related traditions, and why careful record-keeping is one of the most underrated disciplines in serious magical practice. From there, we will move into the practical systems that allow a spellbook to function not as a scrapbook, but as a true working archive.

For much of human history, writing itself was experienced as a form of enchantment. In societies where literacy was rare, written marks were not simply information — they were invisible speech made durable. A book could speak without a speaker. A mark on a page could carry a voice across distance and time. To open a book was to hear someone who was not present. To copy a text was to participate in a chain of transmission that could outlive any single life.

It is not accidental that magical traditions gravitated toward written records. Long before grimoires existed as a category, writing already carried authority, mystery, and power. Sacred texts, legal documents, and technical manuals alike were treated as charged objects because they held speech in a fixed and repeatable form. The book itself became a vessel — not just for knowledge, but for legitimacy, memory, and continuity.

Grimoires inherit this cultural and symbolic weight. They are not powerful only because of what they contain, but because of what they are: objects designed to stabilize knowledge, to preserve procedures, and to allow precise transmission. In this sense, a grimoire is already a kind of spell. It binds voice to matter. It makes memory persistent. It allows a practice to become lineage rather than improvisation.

Modern witches may work with hand-bound books, binders, digital archives, or hybrid systems. The form changes. The function does not. A written spellbook remains a technology for making magic repeatable, testable, and transmissible. It is one of the ways the craft moves from inspiration into discipline.

Touchstone

Historians of magic and literacy have long noted that written texts carried social authority precisely because they preserved speech beyond the body, transforming personal knowledge into transmissible technique. This function of writing — stabilizing and transmitting specialized knowledge — is foundational to how magical traditions develop technical lineages over time.

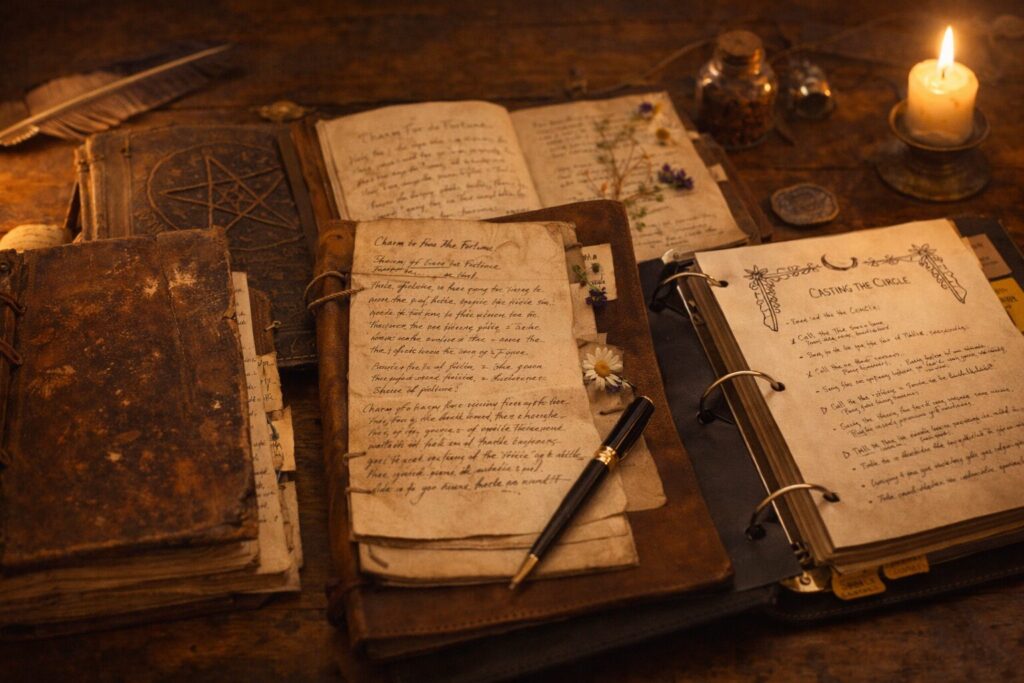

Within modern witchcraft, two overlapping lineages of magical books are most commonly referenced: the grimoire and the Book of Shadows. While the terms are often used interchangeably today, they arise from different historical and cultural streams.

Historically, grimoires were technical manuals of ritual magic. They emphasized procedure, precise wording, timing, and method. These books were often copied, adapted, and expanded by hand. Marginal notes, corrections, and variations were common. In this way, grimoires functioned less as static scriptures and more as working documents — shaped by practice, transmission, and revision.

The Book of Shadows, by contrast, is closely associated with the development of modern Wicca and contemporary witchcraft traditions. It typically blends religious material, ritual outlines, ethical teachings, and spellwork. In many Wiccan lineages, the Book of Shadows also carries initiatory and coven-specific material and may be treated as oath-bound or restricted. It is both devotional and technical, combining spiritual worldview with working practice.

Modern witches often blend these two streams. A contemporary Book of Shadows may function very much like a grimoire in practice, while a grimoire may include devotional material that would once have been associated more closely with religious texts. The boundaries are porous. What matters most is not the label, but the function: a working book that preserves tested methods, records results, and supports continuity of practice.

At Coven of the Veiled Moon, we honor both lineages. We recognize the Wiccan Book of Shadows as a central influence within modern witchcraft, and we also recognize the older technical traditions of grimoires as part of the broader magical heritage. In practice, our approach treats the spellbook as a living working document — shaped by experience, grounded in record-keeping, and refined through testing.

Touchstone

Modern scholarship on Wicca and contemporary Paganism emphasizes the Book of Shadows as a defining feature of ritual transmission, while studies of early modern magic highlight grimoires as technical manuals that evolved through copying, annotation, and practical adaptation. Together, these streams demonstrate that magical books have long functioned as living documents rather than fixed authorities.

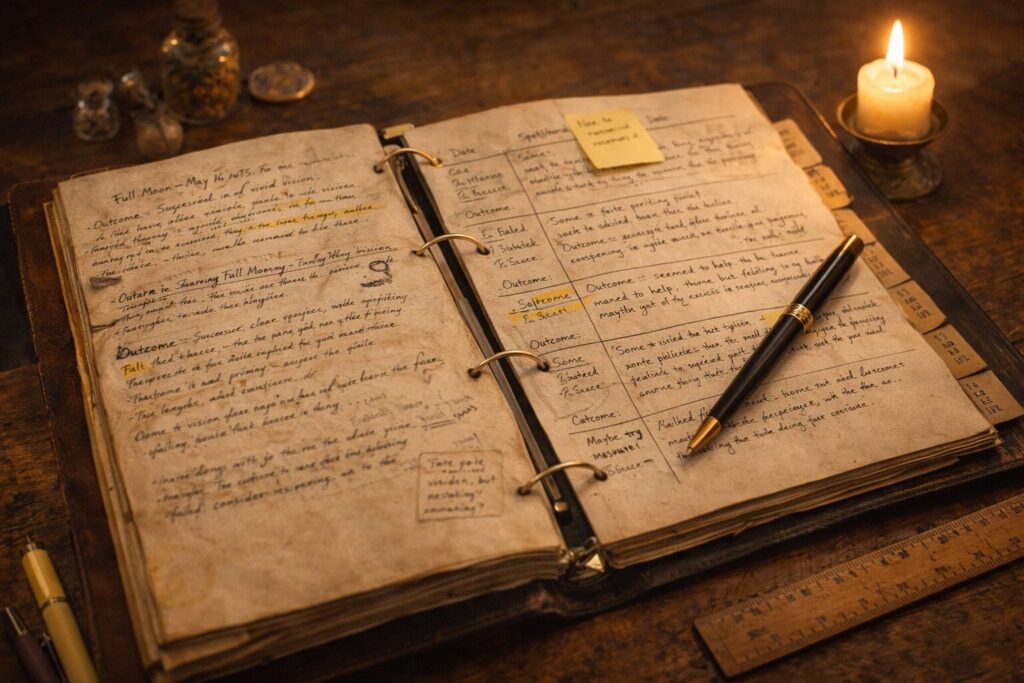

One of the clearest marks of a maturing practice is the shift from inspiration to documentation. Early in the craft, it is common to rely on memory, intuition, and scattered notes. Over time, serious practitioners discover that memory is selective, intuition is shaped by bias, and undocumented work is difficult to evaluate honestly.

A working spellbook introduces accountability. It allows a practitioner to see what was actually done, not just what was remembered. It makes patterns visible over time. It reveals which methods consistently work, which only work under certain conditions, and which fail altogether. In this sense, the book becomes a mirror of practice. It reflects not only successes, but habits, assumptions, and blind spots.

This is why careful record-keeping is not bureaucratic. It is magical discipline. Writing down a working forces clarity. Recording outcomes forces honesty. Revisiting past entries reveals growth — or stagnation. A spellbook that contains only polished successes becomes a performance piece. A spellbook that contains experiments, failures, revisions, and learning becomes a true working tool.

At MCC, we treat the grimoire and Book of Shadows as instruments of magical maturity. They are places where practice becomes traceable, where learning becomes cumulative, and where craft moves from isolated acts into coherent development. This is the foundation upon which everything else on this page rests: the understanding that writing is not secondary to magic, but one of the ways magic becomes durable.

Touchstone

Scholars of ritual and embodied practice consistently emphasize that repeated, recorded action transforms belief into technique. In magical traditions, written records function as both memory aids and instruments of refinement, allowing practitioners to move from isolated experiences into sustained, transmissible craft.

Working Records & Supporting Books

A spellbook is a working manual. A journal and dream book support the craft without burying it. Use these sections to keep your records clear, searchable, and alive.

The Spellbook and the Journal: Why Not Everything Belongs in the Grimoire

One of the most common mistakes in magical record-keeping is collapsing every kind of writing into a single book. While this may feel convenient at first, it often leads to confusion, clutter, and loss of clarity over time. A spellbook is a working technical manual. A journal is a reflective space. When these functions are merged without distinction, both suffer.

The spellbook exists to preserve working knowledge: spells, rituals, procedures, correspondences, and tested methods. Its purpose is to make magic repeatable and transmissible. For that reason, it benefits from structure, consistency, and restraint. Entries should be clear, legible, and focused on what was done and what resulted.

A magical journal, by contrast, serves a different function. It is a place for reflection, emotional processing, observation, and personal meaning-making. It may include feelings, spiritual questions, shifts in belief, and the interior experiences that accompany practice. This material is valuable, but it is not the same as technical instruction. Placing it in a separate journal protects the spellbook from becoming emotionally saturated and protects the journal from being constrained by technical formatting.

This separation is not about hierarchy. It is about clarity. When a practitioner can open their spellbook and see only working material, the book remains usable as a tool. When they open their journal, they can engage fully with reflection without worrying about disrupting technical records. Over time, this division supports both emotional integration and technical refinement.

Many experienced practitioners maintain multiple books for this reason. The spellbook becomes a reference. The journal becomes a companion. Each serves the other, but they are not the same.

Magical Journaling: Observation, Reflection, and the Craft of Noticing

Magical journaling is the discipline of paying attention in writing. It is where the interior and exterior dimensions of practice meet: mood, timing, intuition, environment, emotional response, and subtle pattern. While the spellbook records what was done, the journal often records what was noticed.

A journal may include reflections after ritual, emotional states before and after spellwork, synchronicities, questions, spiritual insights, and shifts in personal understanding. It is a place to track one’s relationship with the craft rather than the mechanics of the craft itself. Over time, this produces a different kind of pattern recognition — one that reveals how personal state, environment, and timing influence experience.

This practice of noticing is not trivial. Many witches discover that their most consistent breakthroughs come not from changing techniques, but from recognizing internal and situational patterns: fatigue, emotional charge, seasonal sensitivity, or environmental influence. Journaling makes these patterns visible.

A journal also provides a safe container for material that may not yet be ready to become technical instruction. Early drafts of spells, half-formed ideas, personal struggles, and exploratory writing belong here. Later, if a working proves effective and stable, it can be formalized and transferred into the spellbook in a clearer, more technical form.

In this way, journaling becomes a kind of compost. It is where raw experience is processed. The spellbook then becomes the place where what has been refined is preserved.

Dream Journaling: The Night Book and Why It Is Best Kept Separate

Dream work occupies a unique place in magical practice. Dreams are often symbolic, emotionally charged, and shaped by the subconscious. They may contain genuine insight, spiritual imagery, or meaningful pattern — but they are also fluid, personal, and highly interpretive. For this reason, they benefit from their own dedicated record.

Keeping a separate dream journal allows dreams to be recorded quickly and honestly, without forcing them into technical categories too soon. A dream book may include sketches, fragmented notes, emotional impressions, and evolving interpretations. It is a space where ambiguity is allowed.

Placing dreams directly into a spellbook can blur important distinctions. Spellbooks require clarity and repeatability. Dreams rarely offer either in their raw form. By keeping dream material separate, practitioners preserve the integrity of both records. The dream book remains a place of exploration. The spellbook remains a place of tested instruction.

Over time, patterns may emerge in the dream journal that are relevant to magical practice. Certain symbols, recurring figures, or repeated themes may suggest spiritual relationships, inner work, or intuitive directions. When a dream insight becomes stable enough to inform a working, it can then be translated into a spellbook entry in a clear, grounded way.

This layered approach respects the different kinds of knowledge involved. It allows dreams to remain what they are — rich, symbolic, and personal — while protecting the spellbook as a technical and transmissible tool.

The Architecture of a Working Grimoire

A serious spellbook is not merely a place to store ideas. It is an engineered system for memory, repeatability, and refinement. These sections outline how a working book is structured so that knowledge does not simply accumulate, but matures.

What Belongs in a Working Grimoire (and What Does Not)

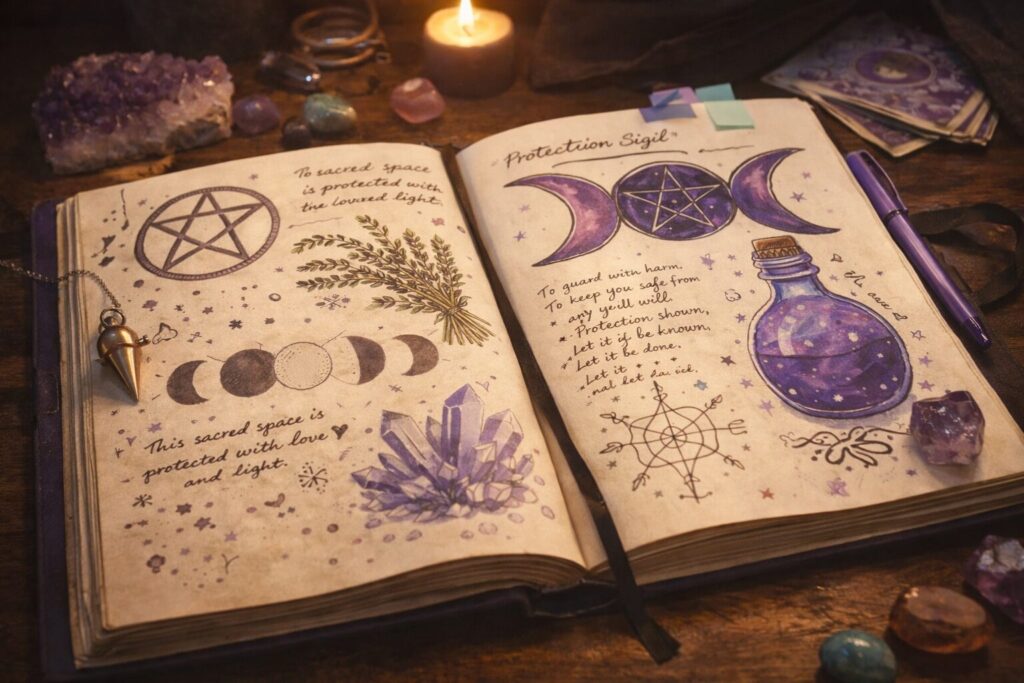

A working grimoire is not a scrapbook, and it is not a diary. Its purpose is to preserve material that can be used again with clarity and reliability. This includes written spells, ritual procedures, timing methods, correspondence systems, sigils, diagrams, maps of ritual space, and structured notes on outcomes and revisions.

The guiding question for any entry should be simple: could another skilled practitioner, or your future self, understand what was done and why? If the answer is yes, the material belongs in the spellbook. If the material is primarily emotional, exploratory, symbolic, or still forming, it belongs in a journal or personal working notebook instead.

This distinction protects the integrity of the book. A spellbook that becomes saturated with raw processing, personal narrative, or speculative writing becomes harder to use as a technical reference. By reserving the grimoire for tested or clearly structured work, you preserve it as a tool rather than a memory box.

This does not make the spellbook sterile. Art, hand-drawn symbols, charts, and visual material often belong in the book when they directly support a working. What matters is function. Beauty is welcome. Confusion is not.

Materials & Binding: Paper, Ink, and the Physicality of Memory

The physical form of a spellbook shapes how it is used and remembered. Paper, ink, and binding are not merely aesthetic choices. They affect durability, legibility, and the ease with which material can be reviewed and revised over time.

Many practitioners find that writing by hand strengthens memory and focus. The physical act of forming words and symbols slows the mind and reinforces intention. Over years of use, a book becomes marked by repetition and presence.

Binding choices matter for long-term practice. A sewn or bound book creates a sense of continuity and gravitas, but it can limit reorganization. A binder or modular system allows pages to be added, removed, or reordered as the system grows.

Ink should be chosen for legibility and longevity. Fading, bleeding, or overly decorative scripts may look appealing at first but can become obstacles after years of use. A working book should privilege readability over ornament.

Secrecy & Protection: Privacy, Locking, and Magical Boundaries

A spellbook contains more than information. It contains patterns of practice, personal power, and in some traditions, ritual relationships. For this reason, privacy is not paranoia. It is part of ethical boundary-setting.

Physical protection may be as simple as keeping the book in a private location, using a lockable case, or storing it in a dedicated space. Magical protection may include warding or other boundary practices according to tradition.

Deciding who may read or handle your spellbook is a serious choice. Even within covens, personal books often remain private.

Physical vs Digital Spellbooks: Memory, Weight, and the Spirit of the Medium

Digital systems offer undeniable advantages: searchability, backups, easy duplication, and rapid editing.

Physical books carry a different kind of memory. A handwritten page holds context, focus, and the accumulated presence of repeated use. Many witches experience this as spiritually significant.

Hybrid systems are common. Digital tools support organization and preservation. Physical books hold the core working material.

Organization as Magic: Indexing, Cross-Referencing, and the Librarian’s Art

Organization strengthens the craft by making knowledge visible and retrievable. Indexes, tables of contents, and cross-references are not mundane habits. They are magical disciplines.

Over time, good organization allows patterns to emerge and methods to refine. Think like a librarian. Protect memory.

Movable Pages and Growing Systems: Expansion Without Chaos

A living practice grows. Systems that cannot expand become cluttered or frozen. Modular formats allow the spellbook to remain usable over long development.

Flexibility supports honesty. A book that can evolve remains aligned with a practice that evolves.

Common Errors in Magical Record-Keeping

The most frequent errors are quiet ones: failing to record outcomes, only writing successes, never revisiting old work, and letting emotional processing replace technical clarity.

A book that is too precious to write in is no longer a working grimoire.

Archiving, Versioning, and Magical Memory

A mature spellbook does not pretend the craft is linear. Workings evolve because practitioners evolve. A method that once succeeded can falter under new conditions, and an approach that once failed can become reliable when the witch has gained steadier focus, clearer timing, or better discernment. That is not a weakness in the craft. It is one of its most honest truths.

This is why archiving matters. Not because it is tidy, but because it allows the craft to remember itself. When you preserve earlier drafts, marginal notes, and revisions, you preserve the path by which a working became trustworthy. A final, polished version may be useful, but it does not teach as well as the trail that led there. The crossed-out line that removed an unnecessary ingredient, the note that a ward held longer when sealed differently, the observation that timing mattered more than expected — these are the moments where practice becomes technique.

If you write a working clearly, revise it honestly, and return later to record what actually happened, the book becomes a record of competence rather than a collection of hopes. Seasonal review deepens this further. By rereading what you have written, you learn which methods remain reliable, which have become situational, and which should be retired.

Retiring a working is not an admission of failure. It is an act of integrity. A living archive stays lean enough to use and honest enough to trust.

Archiving is an act of respect: respect for the work, respect for the learning, and respect for the truth that craft is made through repetition and refinement.

The Coven Archive: The Living Grimoire of the Veiled Moon

In addition to personal books, we maintain a coven grimoire. This is a shared archive of tested and approved workings. It is not a dumping ground for ideas, and it is not a scrapbook of aesthetic spells. It is a living manual of what the coven has actually practiced, refined, and verified through experience.

Entries are added through testing, discussion, and collective agreement. Sources are cited. Attributions are preserved. Errors and failed versions are not erased, but retained as part of the learning record. This allows the coven book to function as a lineage document rather than a highlight reel.

Each member maintains their own personal book. The coven grimoire is not a replacement for individual practice. It is a shared memory. It preserves what has proven reliable within this specific body of practitioners and this specific tradition.

In this way, the coven archive becomes more than a reference. It becomes a vessel of continuity. It carries the accumulated discipline of the group forward so that the work does not have to be rediscovered from scratch each generation.

A spellbook is never finished — not because it is lacking, but because the craft itself is alive. As practice deepens, the book becomes a place of accumulation and invention, a workshop where methods are refined, symbols are shaped, and ideas are tested against experience. Its pages begin to carry not only what has been learned, but the distinctive style of the practitioner who keeps it.

Over time, a well-kept book becomes a pleasure to return to. It is a place where patterns emerge, where favorite methods reveal themselves, and where the hand remembers what the mind might forget. The book becomes a creative space as much as a technical one — a place to sketch, to map, to annotate, to revise, and to play seriously with the forces and forms of the craft.

This is one of the quiet joys of long practice. The book grows alongside you. It thickens with use. It develops its own internal logic, its own rhythm, its own familiar paths. Opening it is not merely an act of reference. It is a return to a working space where imagination and discipline meet, and where ideas are given the chance to become effective realities.

Whether kept in a single bound volume, a modular system, or a hybrid archive, the spellbook becomes a personal laboratory and a private library. It holds not only what you have done, but what you are capable of doing next. It becomes a place where curiosity is rewarded, where experimentation is recorded, and where success leaves a trail that can be followed again.

In this way, the book is not only an archive of the past. It is an invitation to future work. It is where the craft stretches its legs, tries new shapes, and discovers what it can become. To keep such a book is not merely to document magic. It is to give the craft a home where it can grow, evolve, and, yes, have some fun doing it.

Continue the Work

“Knowledge unrecorded is knowledge soon lost” -Agrippa