Reading Tea Leaves

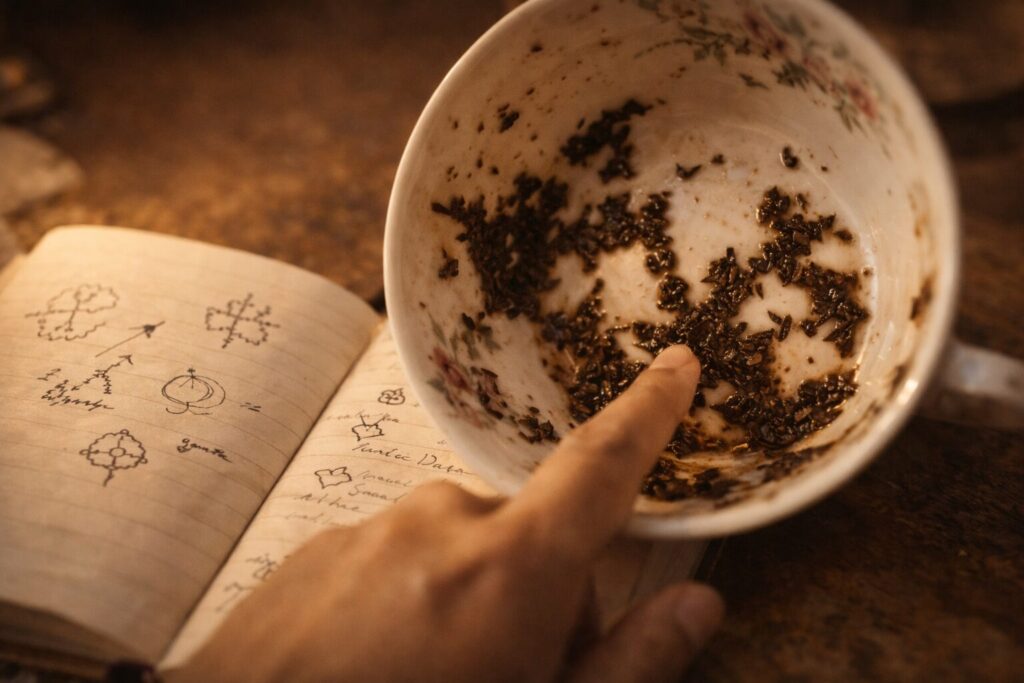

To read tea leaves is to practice one of the most intimate forms of divination: an oracle hidden inside an everyday act. A cup is brewed, shared, emptied, and only then does its secret appear. Unlike systems built from formal decks or carved symbols, tasseography emerges from residue — the trace left behind after use. It is a divination of aftermath, of what remains when intention has passed through matter. In this sense, tea leaf reading belongs to a domestic lineage of magic where the ordinary world is not separate from the sacred, but saturated with it.

Historically, the practice flourished in spaces of conversation rather than temples: kitchens, parlors, traveling camps, communal gatherings. A cup passed from hand to hand carried more than warmth; it carried story, timing, and subtle diagnosis. The leaves became a shared language through which private concerns could be spoken indirectly. Because the symbols arise from chance rather than inscription, every reading is collaborative. The cup offers a pattern; the reader brings interpretation; meaning emerges between them.

Tasseography is often mistaken for light entertainment, yet its mechanics are austere. There is no elaborate toolset to hide behind — only a vessel, sediment, and attention. The reader must learn to see proportion, density, direction, and rhythm in irregular shapes. A cluster is read differently from a single mark; a symbol near the rim carries different weight than one buried at the bottom. The discipline lies in noticing without forcing, allowing the pattern to declare its tone before assigning narrative.

Within witchcraft, tea leaf divination occupies a unique position. It bridges hospitality and ritual. The act of brewing becomes preparation; the act of drinking becomes intention-setting; the act of reading becomes revelation. Herb, water, fire, and vessel collaborate in a small, complete cycle. The oracle does not interrupt daily life — it arises from it. In this way, tasseography teaches a quiet lesson shared by many folk traditions: the sacred does not require distance. It waits in the cup already in your hands.

Tea leaf divination is a method of reading pattern rather than predicting fixed events. The leaves do not contain pre-written messages waiting to be decoded; they create a field of shapes that the reader interprets through proportion, placement, and relationship. The practice belongs to the wider family of lot divination, where chance arrangement becomes meaningful through attention. What distinguishes tasseography is its scale. The symbols are small, irregular, and intimate. The reader must work close to the surface, studying texture and density rather than dramatic figures.

A finished cup contains several layers of information at once. Some leaves cling to the rim, suggesting influences already near consciousness. Others stretch along the sides, indicating currents unfolding in time. Sediment pooled at the bottom points toward root conditions — the slow forces that shape events beneath visible motion. The reading is less a picture than a landscape. One does not hunt for a single symbol; one observes how the terrain is arranged.

This method requires a different kind of literacy than card systems. Cards present curated images designed to communicate archetype. Tea leaves present ambiguity. Their power lies in resistance to neat categories. A shape may resemble a bird, a path, a knot, or nothing recognizable at all. Meaning arises from tone and emphasis as much as imagery. The reader learns to ask: Is this pattern dense or open? Rising or collapsing? Clustered or solitary? These qualities often speak louder than figurative resemblance.

Because tasseography depends on subtle observation, it trains patience. The cup rewards slow looking. Rushing the interpretation produces cliché. Sitting with the pattern allows nuance to emerge. In this way, tea leaf reading functions as both divination and discipline: a practice of learning to see before deciding what is seen.

Tools & Setup

Tea leaf divination begins with materials that encourage clarity rather than spectacle. The ideal cup is light inside and rounded at the base, allowing leaves to settle visibly instead of vanishing into corners. Thin porcelain or ceramic works better than heavy stoneware; the interior surface should reflect light, not swallow it. A matching saucer is useful for traditional inversion methods, though not strictly required. What matters most is visibility. The cup must function as a small landscape the eye can travel easily.

Loose leaf tea is essential. Bagged tea is milled too finely to produce readable structure, though some practitioners open bags and add additional leaves to restore texture. Medium-cut leaves tend to cast the clearest patterns: large enough to hold shape, small enough to distribute across the surface. Herbal blends introduce another layer of symbolism, but their magical associations should not overshadow the reading itself. The leaves are first and foremost a medium of pattern.

Lighting and posture influence interpretation more than many beginners expect. A calm, steady light reveals density and contrast; flickering shadows distort proportion. The reader should be seated comfortably, able to hold the cup without strain. A notebook nearby encourages documentation. Photographing a cup before interpretation can reveal details missed in the first glance and allows comparison over time. Tea leaf divination grows sharper when patterns are tracked, not merely remembered.

Timing also matters. A rushed reading tends to project anxiety into the cup. A deliberate brewing process — pouring water with intention, allowing the tea to steep fully, drinking without distraction — establishes rhythm. The divination begins before the cup is empty. The mood of preparation shapes the clarity of what follows. In this sense, tasseography is less about tools than about attention. The materials are simple; the discipline lies in how they are handled.

The Rite of the Cup

A tea leaf reading begins with a question held lightly rather than forced. The intention should be clear but not rigid — a frame for observation, not a demand for outcome. Questions that ask about movement, influence, or direction tend to produce the most readable cups. As the tea steeps, the reader allows the mind to settle into the rhythm of the act. Brewing is not separate from divination; it is the first phase of it.

The tea is drunk slowly, leaving a small pool of liquid and leaves at the bottom. When only a mouthful remains, the cup is taken in the non-dominant hand — traditionally the receptive hand — and gently swirled three times clockwise. This motion distributes the leaves along the inner surface, creating the field of symbols. The cup is then inverted onto the saucer and left to drain. During this pause, the reader does not rush ahead. The brief stillness allows excess liquid to escape and the pattern to settle into its final form.

When the cup is lifted again, the reading begins at the handle. The handle represents the self: the axis of personal agency. From there the eye travels around the rim, then down the sides, and finally into the base. This order mirrors the movement of time from immediate influences to deeper currents. The reader studies density first — where the leaves gather thickly or thin out — before searching for recognizable figures. Tone precedes image. The emotional weight of a cup is felt before it is named.

Interpretation unfolds as a conversation between observation and intuition. No single shape stands alone. A figure near the rim may be supported or contradicted by what lies beneath it. A dense bottom paired with an open upper cup suggests pressure releasing; the reverse suggests accumulation. The reader resists the urge to finalize meaning too quickly. The cup is read as a whole ecosystem, not a collection of isolated symbols.

When the interpretation concludes, the leaves are discarded respectfully, often rinsed away under running water. Some practitioners thank the cup aloud or touch the rim in acknowledgment. These gestures are not superstition; they close the circuit of attention. The divination ends where it began: with deliberate awareness of the act itself.

The Reading Map

A tea cup is not read as a flat image. It is a vertical landscape in which position carries temporal and emotional weight. Where a symbol appears is often more important than what it resembles. The rim, the sides, the base, and the handle form a coordinate system through which the reading unfolds. Without this structure, interpretation drifts; with it, the cup becomes legible.

Leaves gathered near the rim speak to immediacy. These marks touch the threshold of the present moment — thoughts already forming, influences about to enter daily life, situations close enough to feel. Symbols here rarely describe distant futures. They belong to the edge of awareness, the place where intention is about to become action.

The sides of the cup represent unfolding motion. Shapes stretching along the walls indicate currents already in progress. They describe relationships, projects, and emotional states moving through time. A rising pattern suggests development or ascent; a collapsing one suggests release or dissipation. The sides are the narrative zone of the cup, where tension and resolution begin to show themselves.

The bottom carries the deepest weight. Leaves pooled here point to root conditions: long-term influences, underlying motives, structural realities that do not shift quickly. A heavy base does not necessarily mean misfortune; it means gravity. Something foundational is at work. A clear or lightly marked bottom suggests openness — the absence of entanglement, or a cycle nearing completion.

The handle anchors the entire reading to the self. Symbols closest to it speak directly to the querent’s agency, home, and personal responsibility. Opposite the handle lies the external world — other people, outside forces, circumstances beyond immediate control. The tension between these two poles often reveals the heart of the message: what belongs to the reader to act upon, and what must be navigated rather than commanded.

Taken together, these zones create a map of timing and relationship. A symbol near the rim and handle speaks differently than the same figure buried at the base and opposite side. The cup is not a picture; it is a geography. The reader travels it, tracing how forces rise, intersect, and settle.

How Shapes Speak

Tea leaves do not present fixed icons. They present gestures. The reader’s task is not to match shapes to a dictionary but to recognize how a form behaves. A mark is read first for its energy, then for its resemblance. A rising line carries a different tone than a falling one. A tight cluster speaks of pressure; an open scattering suggests diffusion. Before the mind names a figure, the body registers its mood.

Figurative shapes — birds, paths, knots, circles — gain meaning through context. A bird near the rim may suggest a message approaching; the same shape buried at the bottom may indicate an idea trapped or delayed. A line that ascends the wall of the cup implies progress; a line that breaks midway implies interruption. The cup teaches through motion. Each figure is less a noun than a verb.

Density matters as much as imagery. Thick sediment indicates emphasis. Sparse markings imply subtlety or transience. Repetition strengthens a message: when similar shapes appear in multiple zones, the cup is insisting. Absence is also a symbol. A wide clear space can speak of release, rest, or a cycle that has emptied itself. Silence is part of the grammar.

Because tea leaf symbols arise from irregular material, ambiguity is inevitable. This is not a flaw but a feature. The reader must tolerate uncertainty long enough for a pattern to cohere. Forcing recognition too quickly produces cliché. Waiting allows nuance to surface. Over time, practitioners develop a personal lexicon — shapes that recur and gather private significance. These personal symbols do not replace shared language; they layer upon it, deepening the relationship between reader and tool.

In tasseography, meaning is relational. A figure is read through its neighbors, its placement, and the emotional tone of the cup as a whole. The leaves speak in conversations, not isolated statements. To read them well is to listen for dialogue rather than hunt for answers.

Practical Tea Leaf Workings

The single-question cup

This is the foundation method. One clear question is held during brewing and drinking. The cup is read without searching for spectacle. The emphasis is tone: density, openness, direction. The reader asks what motion dominates the cup and how it relates to the question.

Relationship reading

When reading about relationships, attention moves between the handle side and the opposite wall. Symbols near the handle speak to personal agency; symbols opposite suggest external influence. Intersecting lines or mirrored figures often indicate mutual tension or shared growth.

The goal is not prediction but diagnosis: what dynamic is active, and where effort belongs.

The seasonal cup

A seasonal reading asks about the tone of the coming cycle rather than specific events. The cup is read as a whole ecosystem. A heavy base suggests work that must be completed before renewal; an open rim suggests opportunities already arriving. This method pairs well with Sabbat reflection.

Troubleshooting a difficult cup

Some cups appear muddy or unreadable. This often reflects rushed preparation or emotional noise. Rather than forcing interpretation, the reader pauses. A difficult cup can itself be the message: agitation, impatience, or overload.

When clarity fails, the correct response is restraint. Drink another cup another day.

History & Cultural Roots

Origins of tasseography

Tea leaf divination developed alongside the spread of tea itself. As loose leaf tea entered Europe through trade, the sediment left in cups invited interpretation. The practice likely evolved from earlier methods of reading grounds, ashes, and residue — forms of domestic sortilege where everyday materials became symbolic surfaces.

The cup transformed into a miniature stage on which chance arranged meaning. Over time, shared symbol languages formed through repetition and storytelling.

Parlor divination and social ritual

By the nineteenth century, tasseography had become embedded in parlor culture. Tea readings offered a socially acceptable space to discuss fears, hopes, and private concerns. The divination functioned as conversation disguised as entertainment. Symbol interpretation allowed delicate subjects to be addressed indirectly.

This social dimension remains part of the practice today. The cup invites dialogue as much as revelation.

Global cousins: coffee, bones, and grounds

Tasseography belongs to a global family of residue divination. Ottoman and Greek coffee ground reading shares nearly identical mechanics. Across cultures, people have read bones, ashes, seeds, and sediment. The common thread is the belief that meaning emerges where matter settles.

The cup is one expression of a much older instinct: to observe what remains after an action and ask what it reveals.

Modern revival and popular culture

In contemporary witchcraft, tea leaf reading has resurfaced as part of a broader revival of folk magic. Its appeal lies in accessibility. No specialized deck is required. The oracle lives in the kitchen. Yet accessibility should not be mistaken for triviality. The practice demands attention and restraint to remain sharp.

Within witchcraft, the tea cup functions as both oracle and vessel. It is not separate from spellwork; it is a continuation of it. The act of brewing already engages elemental collaboration: water heated by fire, herbs carrying their own correspondences, steam rising as breath. When intention is held during preparation, the cup becomes a small working before it is ever read. The divination emerges from a ritual already in motion.

Many practitioners choose teas deliberately, aligning blends with purpose. A calming herb before a difficult conversation, a strengthening brew during recovery, a visionary blend for meditation — these choices do not dictate the reading but color its tone. The leaves carry their botanical history into the cup. When interpreted afterward, the shapes sit inside a web of correspondences that extends beyond image alone. Herb and symbol speak together.

Tea reading also lends itself to the “read and respond” loop common in practical magic. A cup that reveals stagnation may inspire cleansing. A cup that shows opportunity may lead to a candle working or written petition. The divination does not end when the cup is rinsed; it suggests action. In this way, tasseography functions as diagnosis followed by remedy. Insight becomes movement.

Because the cup is domestic, it anchors magic in ordinary rhythm. It resists the idea that ritual must be dramatic to be effective. A kettle on the stove, a quiet moment at a table, leaves settling into pattern — these gestures weave divination into daily life without spectacle. The sacred does not interrupt routine; it inhabits it.

Tea leaf divination is gentle in appearance but sharp in implication. Because the practice arises from an everyday act, it can slip unnoticed into habit. A cup read occasionally sharpens perception; a cup consulted compulsively dulls it. Ethical tasseography depends on restraint. The leaves are meant to illuminate a moment, not replace judgment. When a reader begins asking the cup to decide every turn of daily life, the oracle has been mistaken for authority.

Agency remains central. The cup describes conditions; it does not issue commands. A heavy pattern may signal pressure, but it does not forbid movement. A bright rim may suggest opportunity, but it does not guarantee success. To treat symbols as mandates is to surrender responsibility under the cover of mysticism. The healthiest readings return power to the querent rather than remove it.

Projection is another risk. Because tea leaves are ambiguous, they easily absorb fear or desire. A reader who approaches the cup already convinced of an outcome will often find confirmation. Ethical practice requires suspicion toward one’s own certainty. The question is not “What do I want to see?” but “What is actually present?” This discipline separates divination from wish-making.

There is also a boundary around repetition. Reading the same question repeatedly erodes clarity. Each cup becomes an echo of the last rather than a fresh surface. A clean reading demands lived experience between consultations. Time must pass; action must occur. Without that interval, the oracle becomes noise.

Ultimately, the limits of tea leaf divination protect its usefulness. The cup is strongest when treated as a mirror, not a master. It reflects pattern so that action can follow. When the leaves are read with humility and restraint, they sharpen awareness without trapping the reader inside them. The oracle exists to return the practitioner to the world, not to replace it.

Tea Leaf Resources

Tasseography benefits from sources that teach observation rather than promise theatrical prediction. A strong tea leaf resource emphasizes patience, symbol literacy, and historical awareness. Because the practice sits at the intersection of folk magic and parlor culture, good texts treat it as both social ritual and disciplined craft.

One of the most influential modern introductions is Rae Hepburn’s Tea Leaf Reading, which organizes symbol interpretation without stripping the practice of nuance. The work is valued not for rigid meanings but for modeling how to look at a cup methodically. For readers interested in the Victorian lineage of tasseography, A Highland Seer’s Telling Fortunes by Tea Leaves remains a historical touchstone. Though dated in tone, it preserves the conversational spirit that shaped the tradition.

Practitioners seeking a bridge between folk technique and modern witchcraft often turn to Cicely Kent’s The Art of Tea Leaf Reading, which frames the cup as both oracle and ritual object. Across these works, the shared lesson is consistency: keep records, compare cups over time, and allow personal symbolism to develop through repetition rather than invention.

A good resource leaves the reader more observant, not more dependent. The goal is to sharpen perception until the cup becomes legible without constant reference.

Tea leaf divination endures because it hides wisdom in the ordinary. A cup is brewed for comfort, conversation, or habit — and within that familiar gesture a pattern appears. The oracle does not demand a temple or ceremony. It waits in the residue of daily life, asking only that the reader slow down long enough to see what remains. In this way, tasseography teaches a subtle discipline: revelation is not always dramatic. Sometimes it is sediment settling into shape.

The danger of such accessibility is overuse. Because the cup is easy to prepare, it is tempting to consult it for every uncertainty. When divination becomes constant, perception dulls. The leaves blur into reassurance-seeking rather than insight. A strong practice keeps the cup occasional and deliberate. It is meant to clarify a moment, not replace thinking. The oracle sharpens judgment; it does not excuse it.

Within witchcraft, tea leaf reading reminds practitioners that magic thrives in domestic rhythm. The kettle, the table, the quiet pause after drinking — these are already ritual spaces when treated with attention. The cup does not remove a witch from the world. It returns her to it with clearer sight. Each reading ends not with certainty but with orientation: a sense of where effort belongs and where patience is required.

In the end, the leaves offer conversation rather than command. They sketch tendencies, reveal emphasis, and invite response. The meaning of a cup is completed only when the reader acts in the world afterward. Divination is not an escape from reality; it is a way of meeting it with greater awareness. The tea cools, the cup is rinsed, and life continues — slightly more legible than before.